Daniel Graña, emerging market equities portfolio manager at Janus Henderson Investors, Matt Doody, emerging market equities analyst, and Jennifer James, emerging market credit portfolio manager, discuss how China’s decarbonisation has the potential to be one of the next major investment themes.

At the 2020 United Nations General Assembly, Chinese president Xi Jinping caught the world’s attention when he stated that his country would target peak carbon emissions in 2030 and seek to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Considering that China, home to the second-largest economy in the world, is the world’s largest carbon emitter and president Xi’s targets are more ambitious than those of other industrialised countries, this initiative has the potential to reframe the global debate on what’s possible when addressing climate change.

Reaching carbon neutrality will not be easy. It will require an overhaul of China’s energy mix and a fundamental shift in the composition of its economy. Yet, it is possible given China’s top-down decision making and its centralised political system.

"Reaching carbon neutrality will not be easy"

Recent history has illustrated that when the country’s central government puts the full weight of its resources behind major initiatives such as those laid out in its Five-Year Plans, even the most aggressive objectives can be achieved.

The investment implications of China’s decarbonisation program are massive. These will play out over decades and there will be winners and losers. Importantly, this mega-theme will reach far beyond China’s shores and impact multiple companies, sectors and asset classes.

It also stands to raise China’s stature in the realm of environmental, social and governance investing. The environmental implications are clear. Decarbonisation would also likely address social factors by creating jobs in value-added technologies and improving the health outcomes and standard of living for both Chinese citizens and those of other countries.

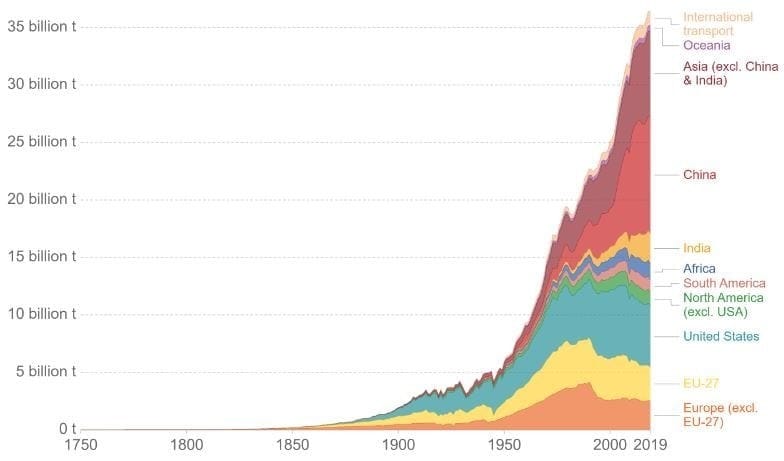

The cost of growth

In China’s rapid ascent to becoming the world’s second-largest economy, it also achieved the more dubious distinction of the largest carbon emitter. The reason for this is clear: developed nations largely offshored much of their manufacturing capacity to the Asian giant that was eager to climb the economic value chain.

Exhibit 1: annual global CO2 emissions (tonnes)

Source: Our World in Data, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC); Global Carbon Project (GCP), as of 31 December 2019.

The conventional assumption is that China placed economic objectives over environmental stewardship as it sought to increase national wealth. To an extent, that may have been true in the past. China burns more coal than any other nation and was responsible for more than a quarter of world greenhouse gas emissions in 2019.

For years, articles on climate change inevitably included photographs of Chinese residents wearing face masks to avoid particulates as heavy, grey fog hung over cities. That image is changing.

In 2013, Chen Jiping, a former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official, remarked that pollution had displaced land disputes as the leading cause of social unrest. Soon after, the National People’s Congress reinforced environmental regulation with the Environmental Protection Law and, in 2015, president Xi announced specific commitments within the framework of the Paris Climate Agreement. Mr. Xi’s recent comments on decarbonisation further codify the central government’s resolve in addressing the climate issue.

The magnitude of the task facing China is illustrated by the persistently high share of the country’s energy mix still attributable to fossil fuels despite a considerable push toward renewables. Over the past three decades, overall energy demand has grown at a 6% annual pace.

As the economy continues to expand, energy consumption will rise along with it. While some progress has been made — hydrocarbons’ share of overall energy demand has fallen from 96% in 1990 to 85% in 2019 — the objective of economic growth, at least in the near term, can only be achieved with a large contribution from fossil fuels.

85%

Hydrocarbon's share of overall energy deman

It’s not just power generation driving hydrocarbon usage. The share of total electricity production attributable to coal has fallen 5% over the past three decades to 66% (over the same period, total renewables’ share has risen from 20% to 31%). However, over a quarter of coal’s usage emanates from industry, including its role as feedstock for steel production.

Time to act

Chinese authorities have chosen now to double down on their decarbonisation commitment because the political and economic calculus is clear and compelling. From the perspective of the CCP, whose hallmark is continuity and stability, it is in China’s best interest to decarbonise as environmental, social, economic and geopolitical factors are all aligned.

From an environmental and social perspective cleaner air equals a healthier, happier and likely more productive population. From an economic perspective, a shift away from fossil fuels to a less carbon-intensive economy offers considerable rewards. Renewables can help remove the reliance on imported fuel — for example, 73% of crude oil consumption in China is met by imports.

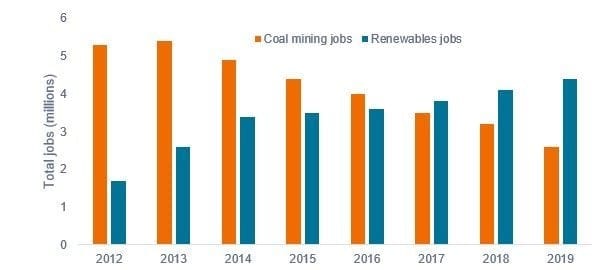

The growth of a home-grown renewables industry also means employment opportunities. This matters because coal mining has historically been an important source of jobs. As the Chinese economy becomes less carbon intensive and those positions go away, they need to be replaced. New opportunities in forward-looking renewables stand to offset lost mining jobs — and in a cleaner, safer and more productive working environment.

Exhibit 2: renewables jobs overtake coal mining jobs in China

Source: IRENA, Bernstein, as of December 2020.

For years, China has sought to gain a foothold in value-added technologies where it could dominate globally. Its push toward renewables presents that opportunity. Already, China is among the leaders in the supply chain for solar and wind technology.

It is positioning itself to do the same with electric vehicles and batteries. With the state creating a conducive environment for innovative renewable tech companies, the country may achieve its goal of becoming a value-added industry leader in a way that has eluded it in other sectors.

Decarbonisation also marries well with China’s policy of “dual circulation.” Greater self-sufficiency in terms of less reliance on foreign suppliers by the upgrading of its manufacturing base and more emphasis on domestic demand and services (internal circulation) acts as a controllable counterweight to foreign trade (external circulation). Chinese companies are also positioning themselves for localisation in overseas renewables markets with partnerships and production by Chinese companies occurring abroad.

China’s decarbonisation push is likely to be aided by its shift toward a less energy-intensive and more service-based economy. The historical driver behind the push toward a vastly different economic composition — favouring consumption and services — has been to increase self-reliance and reduce its exposure to the whims of the global business cycle. Greater consumption and more service also align with the government’s climate objectives as economies with such a composition tend to have a smaller carbon footprint relative to its economic output.

"China’s decarbonisation push is likely to be aided by its shift toward a less energy-intensive and more service-based economy"

Geopolitically, decarbonisation has the potential to achieve two important objectives: It addresses the country’s strategic vulnerability of being a net energy importer and it can increase its sway by becoming a leader in an increasingly important industry. With respect to the former, China is already the global leader in solar and wind production capacity. Despite its already sizable renewables footprint, the country is still reliant on coal for electricity production. Despite ample coal deposits, China must import coal to meet its base load needs.

By expanding its renewable electricity generation capacity — including nuclear and hydroelectric for base loads — the country will further decrease its reliance on imports. With respect to technological leadership, as the demand for renewable energy capacity grows globally, innovative Chinese companies and the central government can leverage their commanding position in these fields to achieve a host of geopolitical ends.

Challenging, but possible

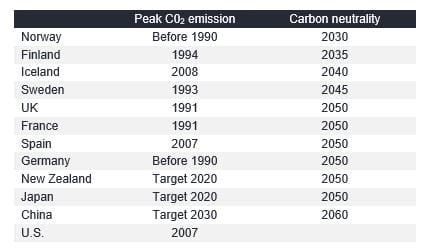

We have seen that there is political enthusiasm, indeed imperative, to decarbonise in China but the targets are challenging. The table below highlights peak emissions and carbon neutrality dates: China intends to achieve in 30 years what many developed countries are taking twice as long to do.

Exhibit 3: calendar of country peak emissions and carbon neutrality

Source: International Energy Agency, World Resources Institute. As of November 2017 for Peak C02 and December 2020 for Carbon neutrality.

China has made progress on shifting the mix and reducing carbon intensity, but the absolute amount of fossil fuel demand remains near peak levels while carbon intensity remains well above that of the developed market.

If China is going to dramatically reduce fossil fuel demand it must formulate policies aimed directly at power generation, transport and industrial sectors. By improving the energy efficiencies of these key sectors, along with the steady ascendency of consumption and services as economic drivers, the composition of China’s economy will look decidedly different in 2060 than it did only a few decades prior.

Together, these factors have the potential to reduce, by some estimates, fossil fuels from 85% of total energy production in 2019 to 25% by 2060, with most of that resulting from the virtual elimination of use of natural gas and coal.

25%

China's 2060 target for fossil fuel energy production

The transition toward more renewables has been aided by a development long in the making: After years of promise, the cost curve of solar and wind generation has dropped considerably, even approaching parity with some traditional power sources.

Not only does this make renewables more cost competitive, it also reduces the need for state subsidies. As the economics of wind and solar allow these sources to stand on their own, electricity generation companies are likely to be more comfortable installing capacity without the fear that a shift in state support will impede their cost dynamics.

This article was originally published on Janus Henderson Investors website.

Disclaimer Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.

CMC Markets does not endorse or offer opinion on the trading strategies used by the author. Their trading strategies do not guarantee any return and CMC Markets shall not be held responsible for any loss that you may incur, either directly or indirectly, arising from any investment based on any information contained herein.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy