Pandemics are not completely random,” says Neil Howe. “They usually break out after periods of global mobility.” Indeed, there’s a long-term correlation between periods of openness and closeness in society, and pandemics can play a significant part in that cycle, he argues.

Howe, a generational theorist, knows this because he has the evidence to prove it — centuries’ worth of data which indicate that throughout history, the human race follows cycles of behaviour that affect our lives, our health, our outlooks, our attitudes to risk… and therefore, yes, our investments.

Take COVID-19, for instance. While the virus has an identified cause and starting point (at least according to the World Health Organization) and ostensibly could have happened at any time, the coronavirus pandemic is also part of a generational pattern, believes Howe.

“It’s true that great pandemics usually break out after long periods of increasing global mobility,” he says. “Look at the Plague of Justinian [a sixth-century pandemic thought to have spread from China, India and Egypt along trade routes], or look at the Black Death, which occurred after we finally opened up the Silk Road. It’s a rough echo, and there is at least the idea that pandemics are not completely random.

“The enormous toll of the Spanish flu caused the 1920s to have that atmosphere, certainly in the US, of completely turning away from foreign policy, and isolationism closing the immigration window. That created a very different mood. There is a long-standing relationship between openness and closeness and pandemics — it’s all part of the cycle”

“And, what you often see historically,” he adds, “is that after a pandemic, we kind of close down a little bit, right? You certainly saw that after the Spanish flu — it wasn’t just everyone’s bad memory of World War I. The enormous toll of the Spanish flu caused the 1920s to have that atmosphere, certainly in the US, of completely turning away from foreign policy, and isolationism closing the immigration window. That created a very different mood. There is a long-standing relationship between openness and closeness and pandemics — it’s all part of the cycle.”

A collective biography

It’s 30 years since Howe, a former public policy advisor who tracked trends in global ageing, long-term social policy and migration, teamed up with US author William Strauss to unveil a theory that societal behaviours repeat themselves about once every 80 to 100 years — about the same time as a long human life.

The Strauss-Howe theory posits that each period, known scientifically as a saeculum, comprises four 20-year generations of societies that always follow the same occurrences and behaviours.

They argued that as each saeculum ends, humankind encounters a crisis, which is followed by 1), a communal commitment to recovery that the authors called a high, then 2), an awakening or a backlash and attack on this community spirit in the name of individualism, which eventually results in 3), an unravelling, or societal and political unrest, which creates conditions for 4), a new crisis — which is where we are now.

The pair’s first book, Generations, which was published in 1991, is lauded and respected as an interesting and relevant theory. Al Gore, the former vice president of the US, said it was the most stimulating book in US history that he’d ever read.

But sharp readers with good memories might also recall it predicted the “Crisis of 2020”, which, while it didn’t specifically identify its nature, warned “it could rival the gravest trials our ancestors have known…” and might result in “some catastrophic failure in the world economy”.

“Each generation views the world differently from their predecessors, not just because they’re older, but because they have lived a different experience — and there are patterns”

No wonder Howe is suddenly in hot demand. “It’s basically a collective biography of each generation, from the Old World settlers coming to the New World,” he says. “Each generation views the world differently from their predecessors, not just because they’re older, but because they have lived a different experience — and there are patterns. One generation comes of age in a war, the next generation are the children during that war, and they have a very different view of what that event meant. And, of course, it shapes them differently and they grow their thinking and feeling differently.

“But certain kinds of generations always follow other kinds of generations. Baby boomers came of age as a very idealistic generation: they wanted to teach the world to sing, and they had all these great ideals for changing morality and culture and values. But they were followed by the notorious Generation X, who started coming of age during the 1980s, and are seen to be very cynical and pragmatic by some. That contrast between a brilliant idealism followed by a kind of cynical, caustic generation is a pattern that goes way back. We tried to apply these patterns, to look at where the US was going.”

“That contrast between a brilliant idealism followed by a kind of cynical, caustic generation is a pattern that goes way back. We tried to apply these patterns, to look at where the US was going”

Boom-to-bust cycles

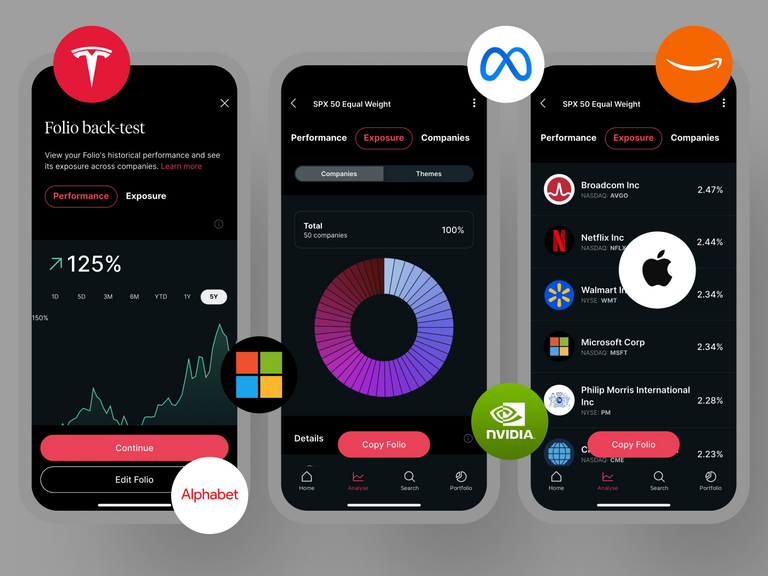

Howe and Strauss (who died in 2007) called each 20–25 year cycle a ‘turning’ — the fourth turning is the crisis — and each one can also predict patterns of investment behaviour. That’s why, Howe believes, the current generation — whose description as millennials was first coined in Generations — are playing the markets more cautiously than their parents and grandparents.

“Millennials tend to be very risk-averse,” says Howe. “They think stocks are risky. One of the reasons ETFs have become so popular is that millennials think they’re like some sort of dedicated, scientific, expert instrument that doesn’t have equities. Which is, of course, ridiculous.” This risk aversion comes from a generation that craves stability, following on, he says, from “older generations who don’t believe in order.

“There’s a kind of menu-driven, optimisation orientation of millennials, who want to get the most expert view, but also have a herd quality, oriented to making sure that they keep up with their community.

“There’s a kind of menu-driven, optimisation orientation of millennials, who want to get the most expert view, but also have a herd quality, oriented to making sure that they keep up with their community”

“I think that actually accentuates what we’re seeing generally in the economy with the growth of the passive-investing ETF mentality — everyone wants to follow the herd. The thing you hear particularly from millennials is ‘I don’t care if I grow poor with all my friends, I just don’t want to be left behind.’”

Howe’s own cycle of life began in October 1951, when he was born in Santa Monica, California. In his late teens and early 20s, he achieved three separate degrees in English, economics and history, all of which fuelled his interest in the links between particular generations and behaviours.

While working in jobs as a public policy advisor to organisations including Blackstone, the Concord Coalition, which is committed to stabilising the US national debt, and the partially state-funded Centre for Strategic and International Studies, he began his ground breaking work with Strauss. He has subsequently authored a raft of other books with such titles as 13th Gen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail?, Millennials Rising and Millennials Go To College. In fact, The Boston Globe called Howe one of the “great American prophets” after publishing The Fourth Turning (which was also co-authored with Strauss).

“I think that actually accentuates what we’re seeing generally in the economy with the growth of the passive-investing ETF mentality — everyone wants to follow the herd”

But it’s his current role that gives him an opportunity to pair his impressive generational insight with stock market trends — as managing director of demography at the Connecticut-based hedge-fund research company Hedgeye.

Generational patterns

So, do particular investments do better than others after a particular turning? What can investors learn from these generational patterns?

“Certainly, the worst periods are the fourth turnings, or crisis points,” says Howe, “which is where we are right now. It’s turning out to be a time of tremendous turbulence.” His research shows that equity markets experienced the highest rate of volatility and lowest CAGR of 1.5% during fourth turnings.

Meanwhile, first turnings are characterised as having the lowest volatility with a CAGR of 6.8%. He adds: “The thing I’m most concerned about now is accelerating inflation expectations, there’s no question about that. I don’t make recommendations for a living, but on my podcast a couple of months ago, I suggested shorting TLT, which is an ETF for long-term fixed rate bonds, nominal bonds, and that was a pretty good call.

“But I think inflation, particularly in the longer term, is not just a problem, it could be a solution, which I think should actually really worry people. Think about it — look at the collateralised bond obligations, the 30-year outlook, not just on economic growth but on fiscal policy, debt and so on. It’s just crazy right now. Even given extremely optimistic assumptions about negative real interest rates for the next few years — rates that are way below nominal GDP growth until the early 2030s — the federal debt is still expected to more than double from its current level. The net financial position of the US is starting to deteriorate extremely rapidly.”

“But I think inflation, particularly in the longer term, is not just a problem, it could be a solution, which I think should actually really worry people. Think about it — look at the collateralised bond obligations, the 30-year outlook, not just on economic growth but on fiscal policy, debt and so on”

However, Howe suggests that certain policymakers may see inflation more as a solution than a problem. “It equalises wealth and incomes. You transfer basically to all the debtors, and you take away from all the creditors,” he states, pointing

to sovereign wealth funds.

“Maybe we care whether China’s central bank experiences losses… but I think the ways in which this could be regarded as a solution should actually worry people even more. If you do see an acceleration of inflation, you will see equities and treasuries being correlated again, moving in the same direction, up or down. And that’s going to be the end of the whole risk-parity approach to investing and further detract from the demand for bonds. They will no longer help you balance your portfolio any more. These are all things to worry about.”

Part of the problem, Howe suggests, with the long cyclical nature of societies and economies is that investors can’t call on their personal experience of previous similar situations. “Not many participants in the markets were around in the late 1970s and early 1980s,” he says. “So, another problem is that we are dealing with an issue that exceeds the current memory of people.”

But, he suggests, society — and therefore the markets — are also shaped by generational attitudes, with every generation having to wait its turn to put down its particular stamp. “The fourth turning is that civic turning point. It’s been kind of a long human lifetime since the Great Depression and World War II, all of the incredible public sector innovations, the redefinition of citizenship that really went on in the 1930s and early 1940s.”

“And here we are back to the fourth turning again. I think everyone feels we’re entering something”

In the intervening decades, he says, the cycles have continued as before. “In the US, we had the awakening — the Age of Aquarius and Woodstock. In China, we had the Cultural Revolution. And in Europe, we had the Baader-Meinhof gang and Euro terrorism.

“And here we are back to the fourth turning again. I think everyone feels we’re entering something. Sometimes decades go by and nothing changes, and sometimes a single year goes by and you get decades’ worth of change. Fourth turnings are when the whole framework of our lives change much faster than they normally do.”

This article was originally published in our Opto Magazine. You can purchase your copy via our Opto Shop.

Disclaimer Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person.

The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.

CMC Markets does not endorse or offer opinion on the trading strategies used by the author. Their trading strategies do not guarantee any return and CMC Markets shall not be held responsible for any loss that you may incur, either directly or indirectly, arising from any investment based on any information contained herein.

*Tax treatment depends on individual circumstances and can change or may differ in a jurisdiction other than the UK.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy