Autonomous vehicles have the potential to completely overhaul transportation, one of the most fundamental elements of our lives. Pedro Palandrani, Director of Research at Global X ETFs, recently joined OPTO Sessions to discuss the opportunities, as well as the safety, regulatory and technological challenges, that are facing the theme.

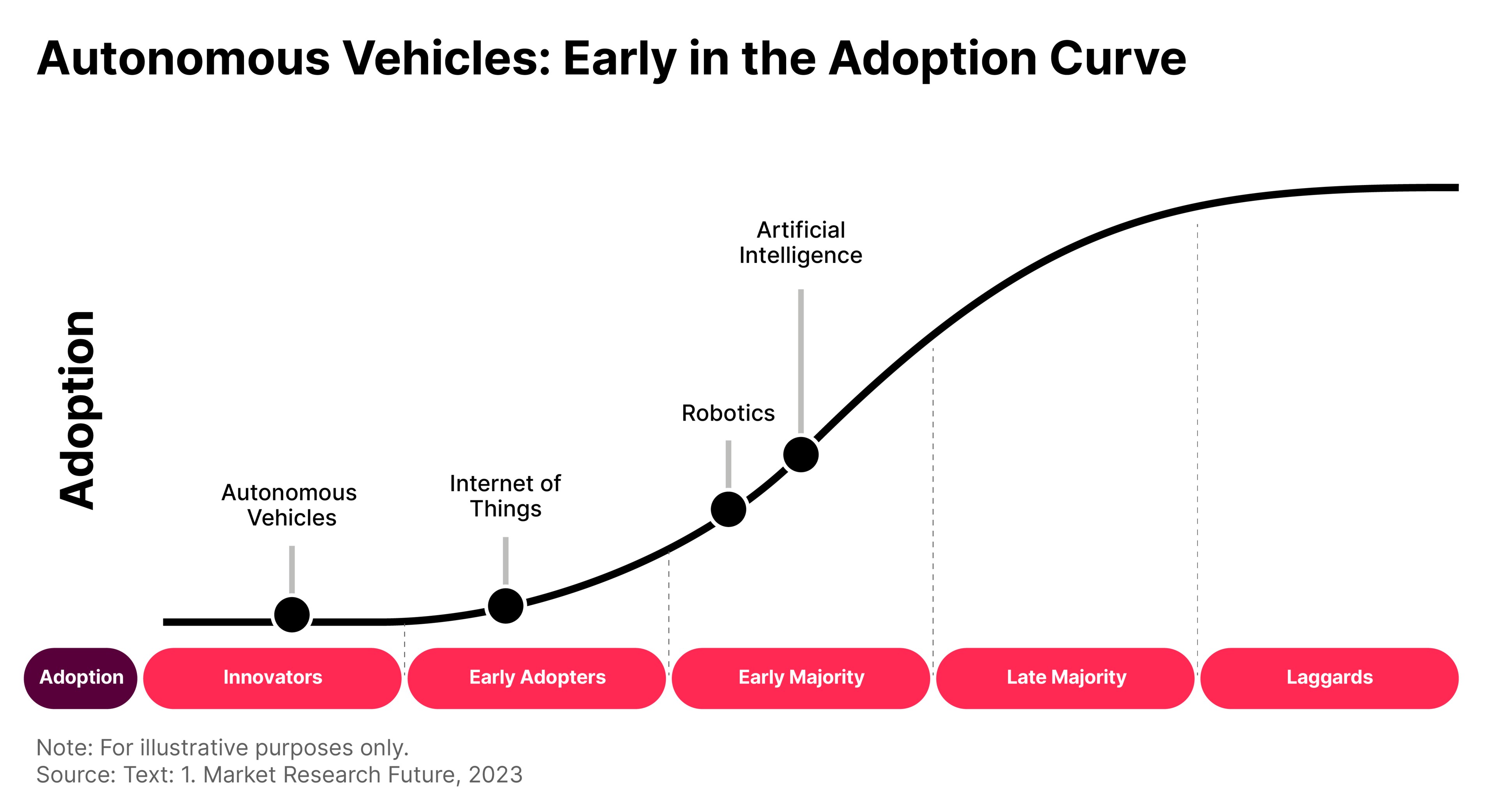

Early in the Adoption Curve

The driverless car is getting closer with every passing day.

According to Pedro Palandrani, Director of Research at Global X ETFs, advances in the technology have the potential to be truly transformative.

While the theme is at present confined to a few geofenced robotaxi pilot schemes, McKinsey research suggests that autonomous vehicles (AVs) are less than a decade away from becoming a major source of revenue for the auto industry.

According to Global X, AVs are early in their adoption curve, especially compared to other related technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and the internet of things (IoT).

Dynamic Changes

In Palandrani’s view, the enormous value-add of AVs stems from the central role of transportation.

“Transportation is very pervasive to our everyday lives,” he tells OPTO Sessions. “We commute daily, and we move goods all around the world at massive scale.”

Given the broad scope of transportation’s impact, its automation — and the productivity, efficiency and safety benefits that could bring — has considerable potential.

“Introducing autonomous systems could drastically change the dynamics of the industry,” says Palandrani.

“Think about the potential impact to productivity when you can have autonomous trucks moving goods 24/7. Think about the potential impact to safety, when vehicle to vehicle communication prevents a car accident.”

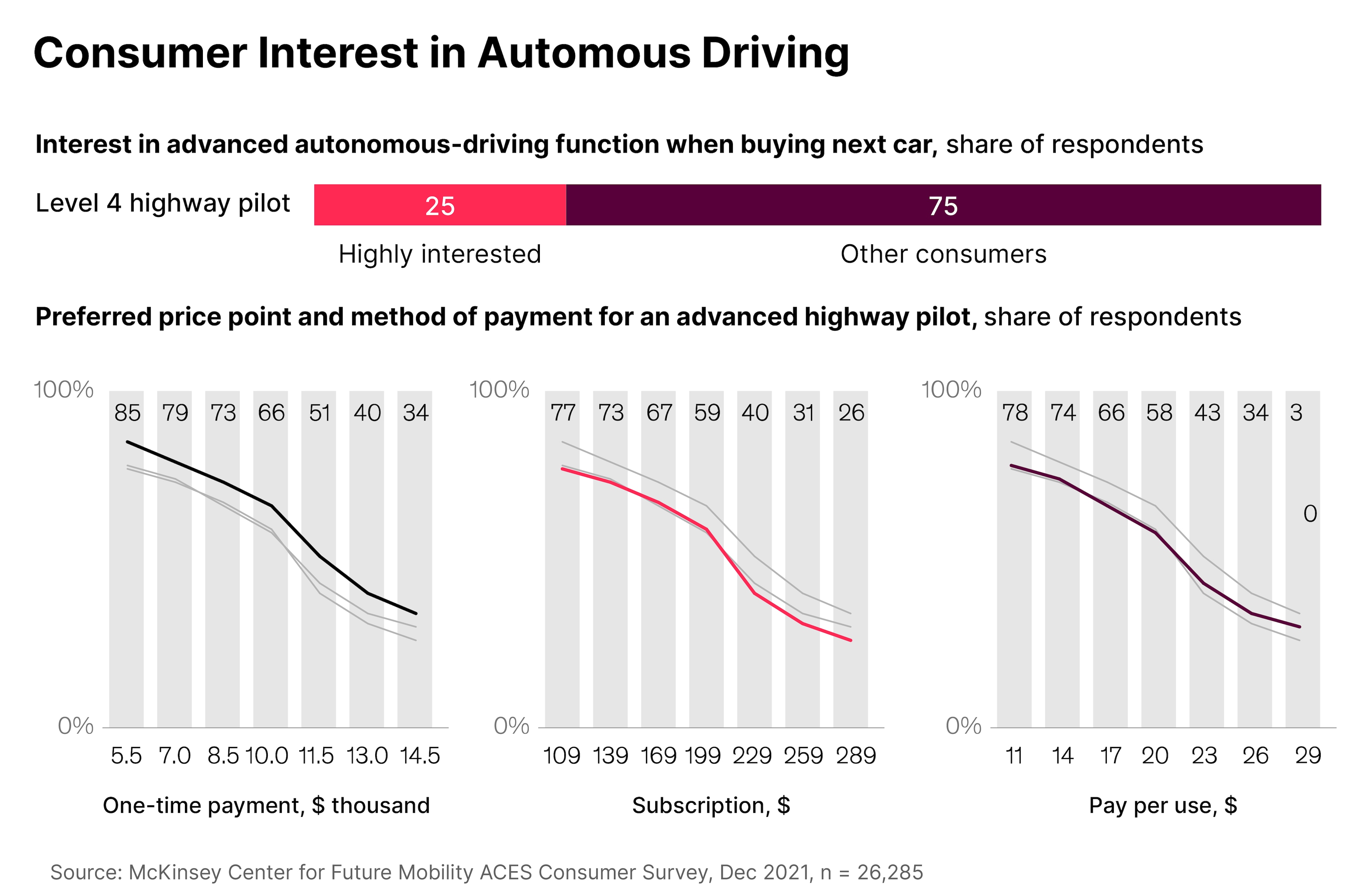

Demand for such systems is increasing. McKinsey estimates that a quarter of drivers are “highly interested” in autonomous driving (AD), with two-thirds of those willing to pay a $10,000 fee for hands-free driving capabilities.

One important consideration is regulation. On the one hand, this could slow progress in the field. However, Palandrani acknowledges that the safety implications make proper regulation of AVs an important consideration.

“We need to take a balanced approach that doesn’t necessarily constrain the progress that we’re seeing in these technologies, while acknowledging that we need to have a thoughtful consideration of their potential risks.”

Lidar of the Pack

There is widely considered to be a hierarchy of five to six levels, through which the technology is progressing:

- Level 0: No automation, fully manual control.

- Level 1: Driver assistance. Palandrani mentions anti-lock braking as an example of this.

- Level 2: Partial automation. Advanced driver assistance systems allow steering and speed to be controlled automatically, but a human driver sits in the driver’s seat and can take control at any time.

- Level 3: Conditional driving automation. The car can respond to its external environment and take “decisions” — for example, to accelerate to overtake a slower vehicle — but, as in level 2, a human driver is always required to be ready to take over.

- Level 4: High automation. The vehicle is in control in most circumstances, and can intervene in the event of a problem or system failure, but the human driver can still manually override the automated system.

- Level 5: The car is fully in control. Level 5 vehicles don’t even require steering wheels or pedals, because the human driver has no involvement. Level 5 cars are not geofenced; they can operate anywhere.

Palandrani points out that the market, in terms of scaled products, is at present mostly around level 2, while the most advanced cars in development are at level 4.

“Level 5 is probably going to take years to see on the road,” says Palandrani. “Level 4 is really the next leg of growth for the industry.”

There is a value chain of interrelated technologies that cascades towards facilitating these self-driving levels. Palandrani breaks this down into three categories:

- Sensors and perception (lidar, radar and cameras)

- Localisation and mapping

- Decision-making (AI and machine learning)

Optimal sensing technology is a subject of vigorous debate in the world of AVs.

Advocates of camera technology, such as Tesla’s [TSLA] Elon Musk, argue that this most closely resembles the way in which humans perceive the world when driving. They also point to the cost benefits of using cameras, which makes the cars cheaper to produce.

However, cameras have some drawbacks compared to light detection and ranging (an approach known as ‘lidar’, which measures the amount of time it takes light to bounce back from surrounding objects) and radar (which operates on the same principle as lidar, but using radio waves). Poor lighting conditions reduce the efficacy of cameras, and to a lesser extent lidar.

Cameras also require a lot of computing power in order to process their input. It is for this reason, says Palandrani, that Tesla has been buying semiconductors at scale.

The optimal solution may be to create hybrid systems that combine two or all three of these technologies. However, Palandrani acknowledges that this would put costs up still further.

Systems and Simulations

AV perception is one question, but the most advanced challenges in the field relate to how autonomous systems make decisions.

Palandrani highlights simulation, and in particular the text-to-video generation opportunities provided by generative AI, as a potential game changer within the space.

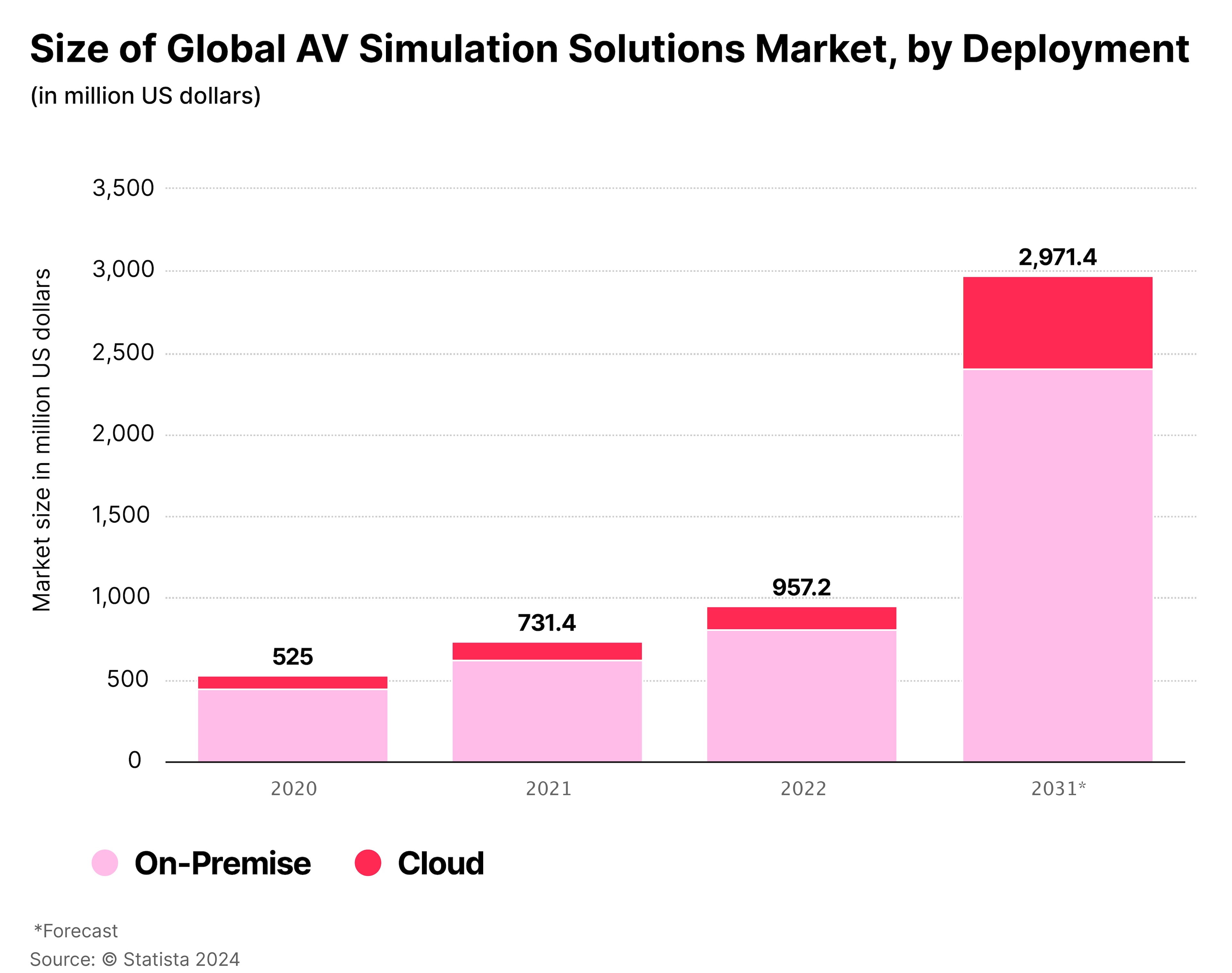

AV simulation is expected to be a nearly $3bn industry by 2031, according to BIS Research. However, one potential limitation is the rare occurrence of events such as extreme weather conditions or aggressive driving, which pose a risk warranting extensive research and testing.

AV systems need to be well-trained in how to respond to these rare, yet particular, scenarios. However, their scarcity in the real-world means there is a paucity of simulation material with which to train models.

Text-to-video technology, in Palandrani’s view, addresses this concern.

“This has the potential to essentially revolutionise how we think about AVs. Once you have text-to-video capabilities, you can start generating a lot of synthetic data,” he says.

“That’s really going to be a driver of growth within the industry.”

A Safe Investment?

Solving the safety concerns around AVs is the number-one priority in terms of the theme’s growth.

The case of General Motors’ [GM] Cruise highlights this point. Cruise suspended its US operations following an accident in October, in which one of its vehicles dragged a pedestrian for 20 feet.

Safety is, for obvious reasons, the number one hurdle for the industry to overcome if it is to gain regulatory approval and build public trust.

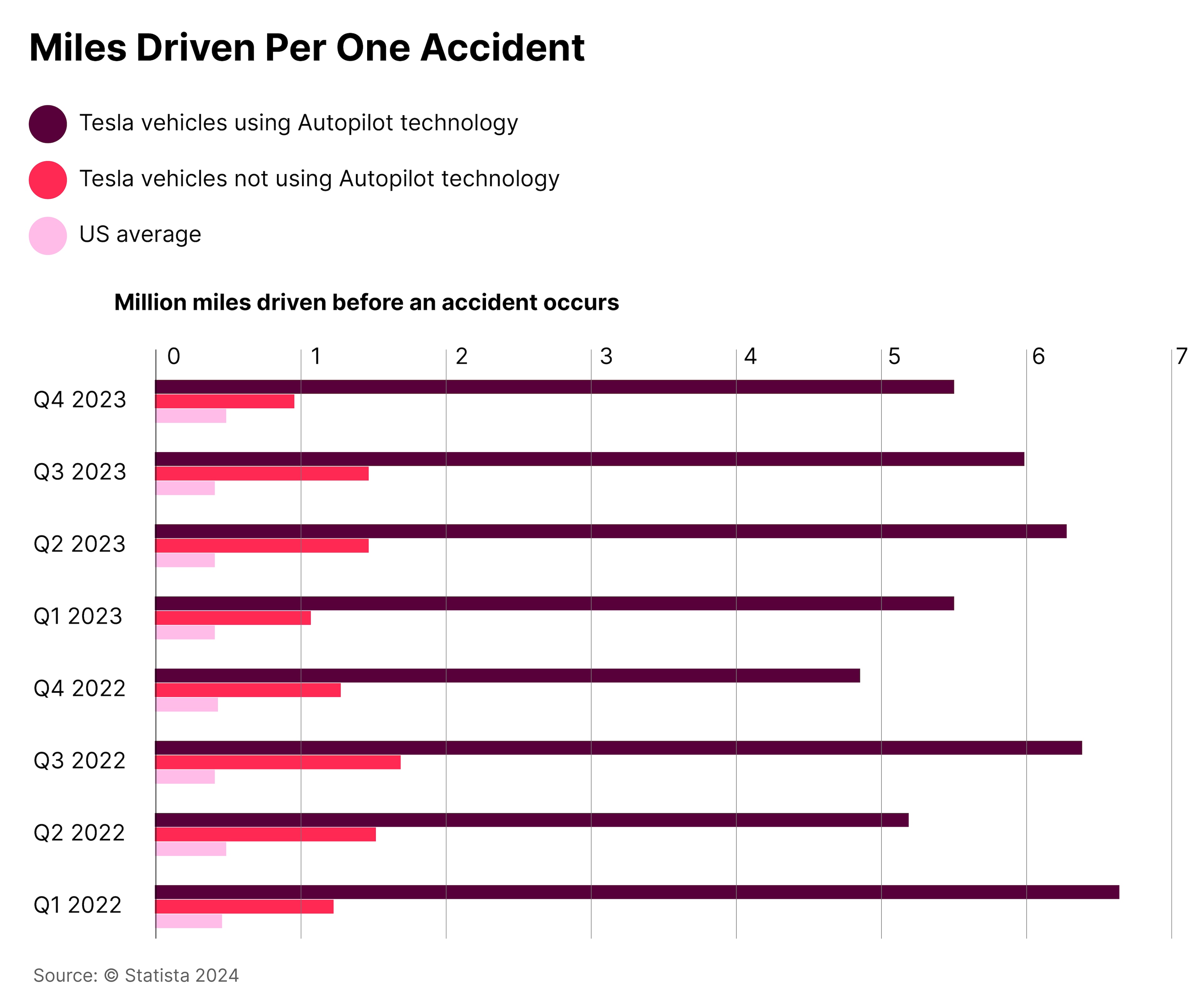

However, the data already accumulated on that front is encouraging. The latest research from Tesla shows that cars using its Autopilot technology covered 5.4 million miles for every crash, compared to the US average of one crash for every 670,000 miles driven.

“It’s an order of magnitude in terms of how much safer these autonomous vehicles can be,” says Palandrani.

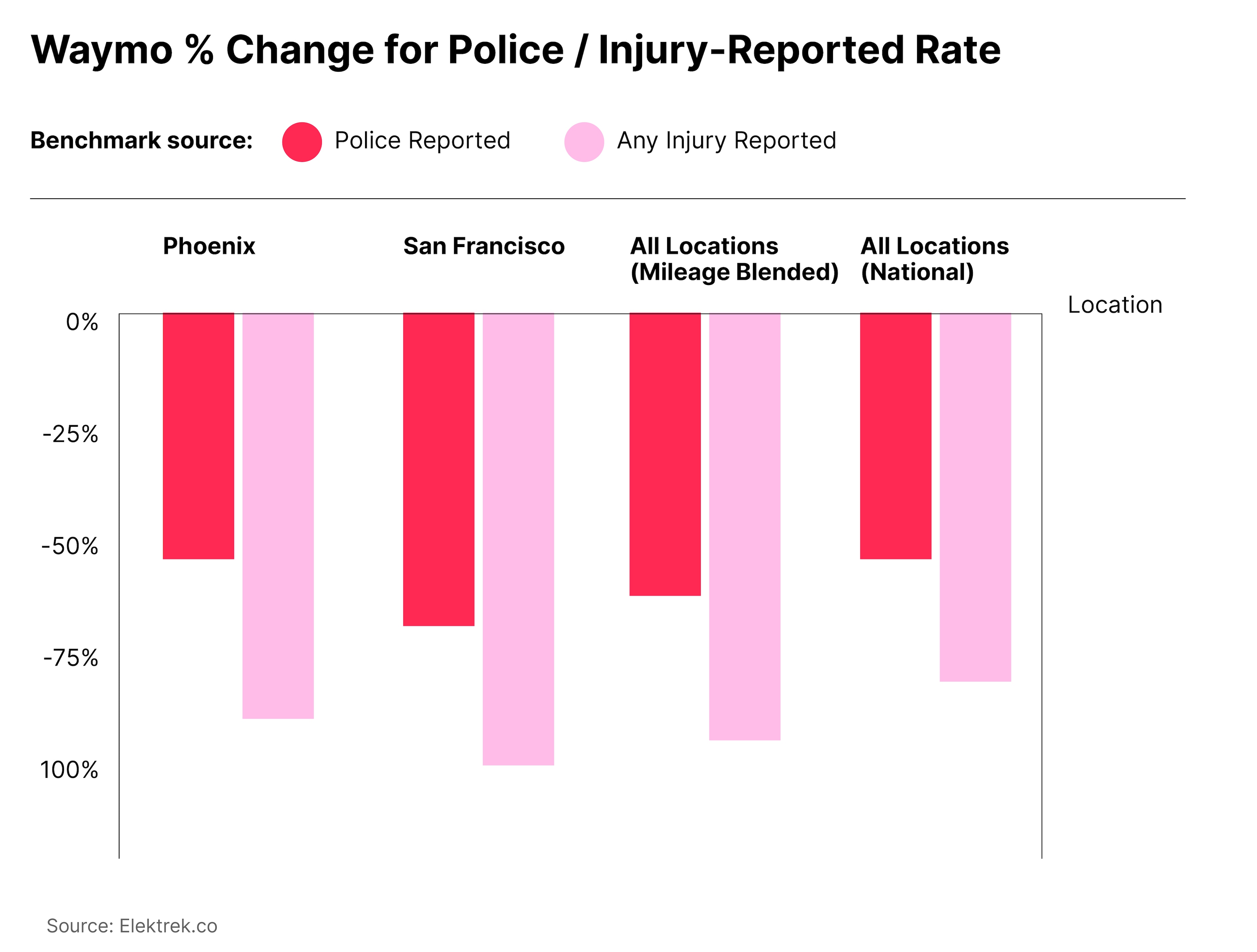

Alphabet’s [GOOGL] Waymo has similarly encouraging figures, reporting an 85% reduction in crashes that caused bodily injury.

Waymo’s research also shows that it’s as much as 10 times less likely to cause injury than human drivers, though instances were reduced in all cases.

“That opens the door to think about, ‘is driving ever going to be illegal?’” says Palandrani.

Given that AVs already seem to be safer than human drivers, the idea that regulators might one day view human error as too great a risk to justify is not as outlandish as it first seems. At the very least, it could lead to a world in which ownership of a vehicle is less and less necessary.

There are other, wide-reaching societal impacts of AVs, too. For example, infrastructure planning has to take into account the future proliferation of these vehicles.

“You definitely need connected or smart cities,” says Palandrani, noting traffic signals that are able to communicate directly to vehicles, as well as to human drivers, should be a prerequisite to widespread AV adoption.

Why Diversification is Key

The AV theme still has plenty of ground to cover. There are only a handful of robotaxi services running globally, and these are heavily geofenced within certain cities, like San Francisco, California, and Phoenix, Arizona.

The US and China are the leaders in trialling the technology, says Palandrani, but Europe is not far behind.

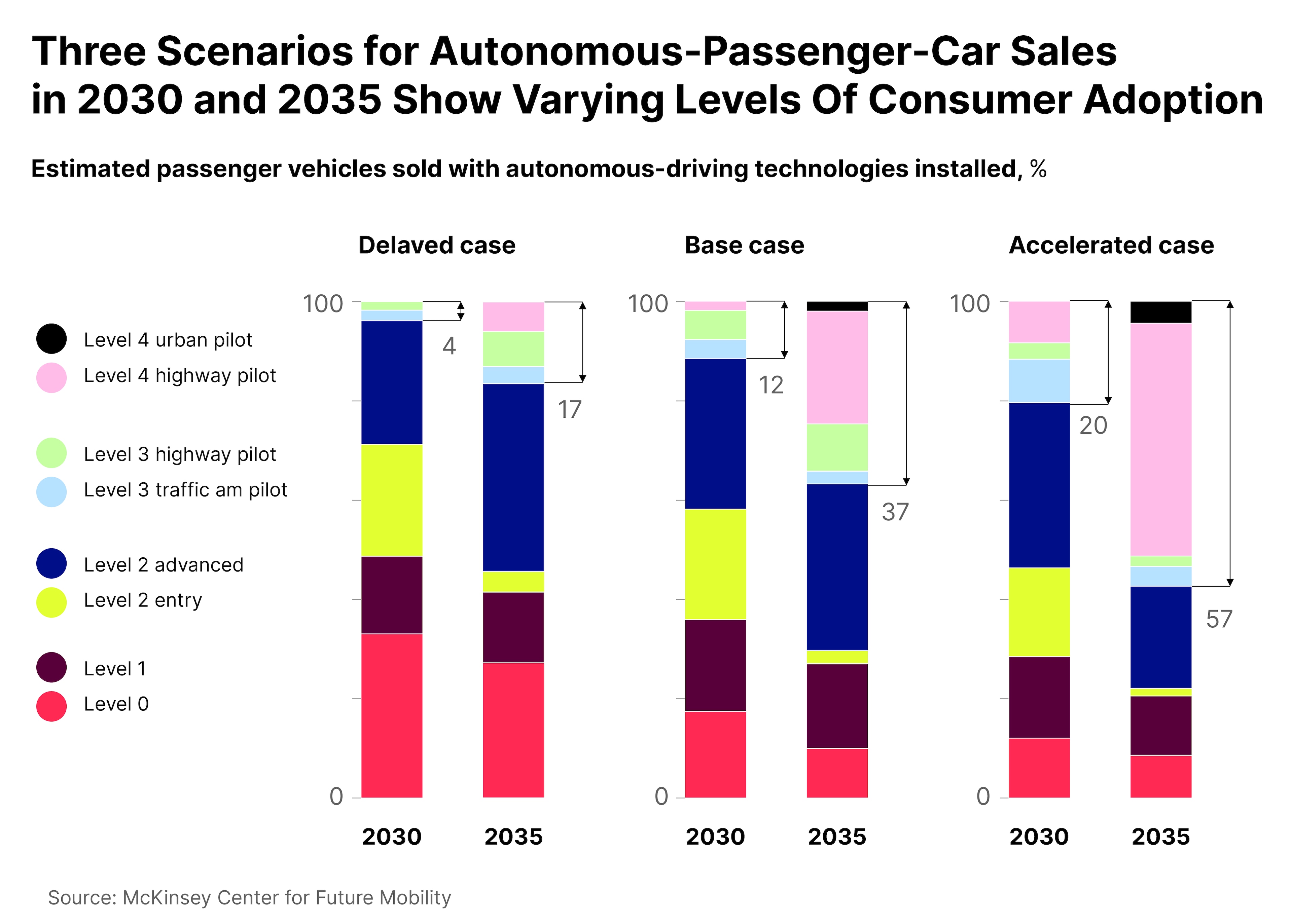

Within a decade, though, it appears likely that AVs could be a major feature throughout the auto industry. McKinsey’s base case for 2030 sees 12% of passenger vehicles sold featuring Level 2 or greater technology, with this number increasing to 37% by 2035. In its ‘accelerated case’, these figures are 20% and 57%, respectively.

For this reason, McKinsey believes that the market for driver assistance and AD systems could reach $400bn by 2035.

Capturing this theme is a complex proposition, says Palandrani. For one thing, the AV market is naturally intertwined with the parallel evolution of electric vehicle technology. Investors in one should consider how they also capture the potential of the other.

He also advocates a diversified approach. The case of Cruise, he says, underscores the risks involved in individual players within this market. “That could happen any day, with any company,” he warns.

The Global X Autonomous & Electric Vehicles ETF [DRIV] captures both trends in a passive, diversified way. It holds Alphabet, Tesla and GM, as of 18 March, as well as Baidu [BIDU], which Palandrani identifies as a leader in China’s AV industry.

DRIV has gained 8.9% in the 12 months to 19 March, and is down 2.9% year-to-date.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy