- an attractive buying opportunity because assets are temporarily depressed due to fear and high-risk aversion, or

- a value trap in which the financial prospects of British companies could continue declining.

If Brexit and the COVID-19 lockdowns are the two main factors responsible for the troubled valuations, will they continue to dampen UK companies’ operations and profits five years hence?

Vaccination, Brexit deal, and mean reversion

The cause of the COVID-19 crisis is biological, and the exit from the crisis will also be biological. The world will emerge from the crisis when the global population achieves herd immunity, halting the ready transmission of the disease. Herd immunity can be achieved through immunisation or in the old-fashioned way as people are exposed to COVID-19 and either contract the disease or exhibit resistance.

Presumably, in the United States and Western Europe, which did not pursue the intrusive contact tracing, enforced quarantines, and closed borders of East Asia and Oceania, a decent share of the population has already been exposed. When most of the rest, the unexposed, have been immunised, the population should approach herd immunity or strong resistance to the virus.

The good news is that several vaccines have shown both safety and efficacy in building immunity against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the COVID-19 pathogen. Creating the vaccines, producing many millions of doses, and administering those doses to the majority of the population in a short time period is a difficult scientific, industrial, and logistical challenge.

That said, the United States alone distributes nearly 200 million flu vaccines each year (an estimated 198 million in the 2020-2021 flu season and 175 million in the previous flu season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). So, the challenge is manageable.

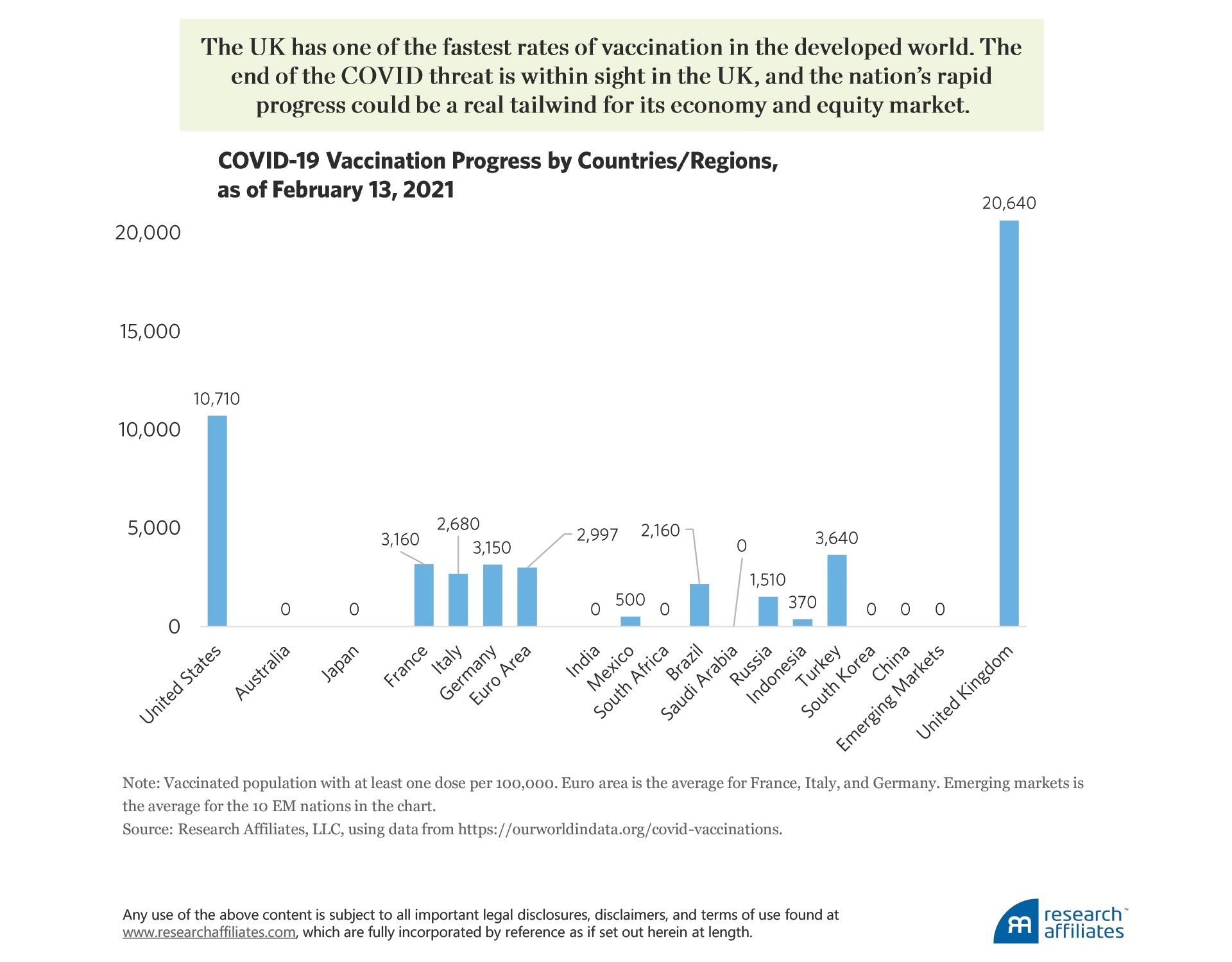

How are different countries coping with vaccination?

As of 13 February 2021, the United Kingdom is a clear leader in vaccination, having vaccinated 20.6% of its population with at least one vaccine dose. The United States is second in the running among the large economies, with 10.7% of the population having received at least one vaccine dose by mid-February 2021, and well over 1 million people “getting the jab” every single day. Other countries, however, significantly lag behind.

The European Union’s progress has been deeply disappointing, with only about 3% of its citizens immunised thus far. Given that most vaccine doses were first delivered in January 2021, the United Kingdom clearly has one of the fastest rates of vaccination in the developed world. The end of the COVID-19 threat is within sight in the UK, and the nation’s rapid progress could be a real tailwind for its economy and equity market.

After the 2016 Brexit referendum, the UK equity market suffered significant headwinds. Uncertainty and fear on numerous fronts caused a decline in UK equity prices: What would be the impact of divorcing from the big and well-integrated European market? What would happen in a no-deal Brexit? How might the EU punish the UK (even if at a cost to its own businesses) to set a negative example to other nations wanting to exit the union? And what other unanticipated outcomes could unfold?

In the UK, 2020 was not all bad news. On the eve of 2021, the UK and the EU reached a long-awaited Brexit deal. The main terms of the deal are:

- tariff-free and quota-free trade;

- continued cooperation on pension benefits and healthcare for mutual visitors; and

- continued cooperation and recognition of the mutual standards.

Are all Brexit-related perils over now for the UK economy?

Not yet. It remains to be seen if the EU will opt for a trade war that would harm future growth for the region. The Brexit deal appears to reduce the likelihood of that scenario, and for each year that passes without new barriers to trade, we believe the prospects for continued free trade are quite good.

With the Brexit deal in place, much of the uncertainty around Britain’s withdrawal from the EU single market and customs union is now resolved. Thus, the Armageddon scenarios envisioned by many on the “remain” side of the debate never materialised. Notably, however, services, which account for the majority of the UK economy, were not included in the final Brexit agreement. This omission is understandably viewed by many as a distinct negative to the Brexit process, particularly as it pertains to financial services.

But as the dust settles on the deal, many have come to believe the exclusion of the services industry will likely be a positive for the City of London. Yes, some jobs have been lost to EU financial hubs, such as Frankfurt, Paris, and Dublin, but not to the extent predicted by many. The trading of Swiss shares is also expected to recommence in London, replacing some of the capital outflows after Britain bowed out of the EU. Optimism now appears strong that the UK can rival global financial hubs such as Singapore and New York.

“The UK equity market stands out as trading cheaper than our last named trade of the decade — the emerging markets.”

The UK’s newfound independence from the European Union allows more flexibility in regulating various aspects of its economy. Just the simple example of the UK’s faster rate of vaccination compared to its European neighbours signals that this new independence may reap benefits going forward.

Such independence of thought when it comes to economic direction and regulation can give the United Kingdom a tailwind in an ever-increasing globally competitive landscape.

Another positive aspect of Brexit is the UK’s freedom to enter preferential trade agreements with other countries and trading blocs. The United Kingdom, on its own, should be more nimble than the EU, which has to agree terms on behalf of 27 different countries, each with its own sovereign process necessary to ratify any deal.

Although some would argue the UK has had a slow start in sealing new trade deals, it will be applying to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a free-trade pact that represents a market of around 500 million people.

The UK already has trade deals with seven of the 11 nations that make up the CPTPP. The potential icing on the cake, however, would be the new Biden administration’s decision for the United States to re-join the CPTPP; the United States withdrew in January 2017. Should the United States not re-join the trading partnership, a trade deal between the UK and the US is likely at the very top of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s to-do list.

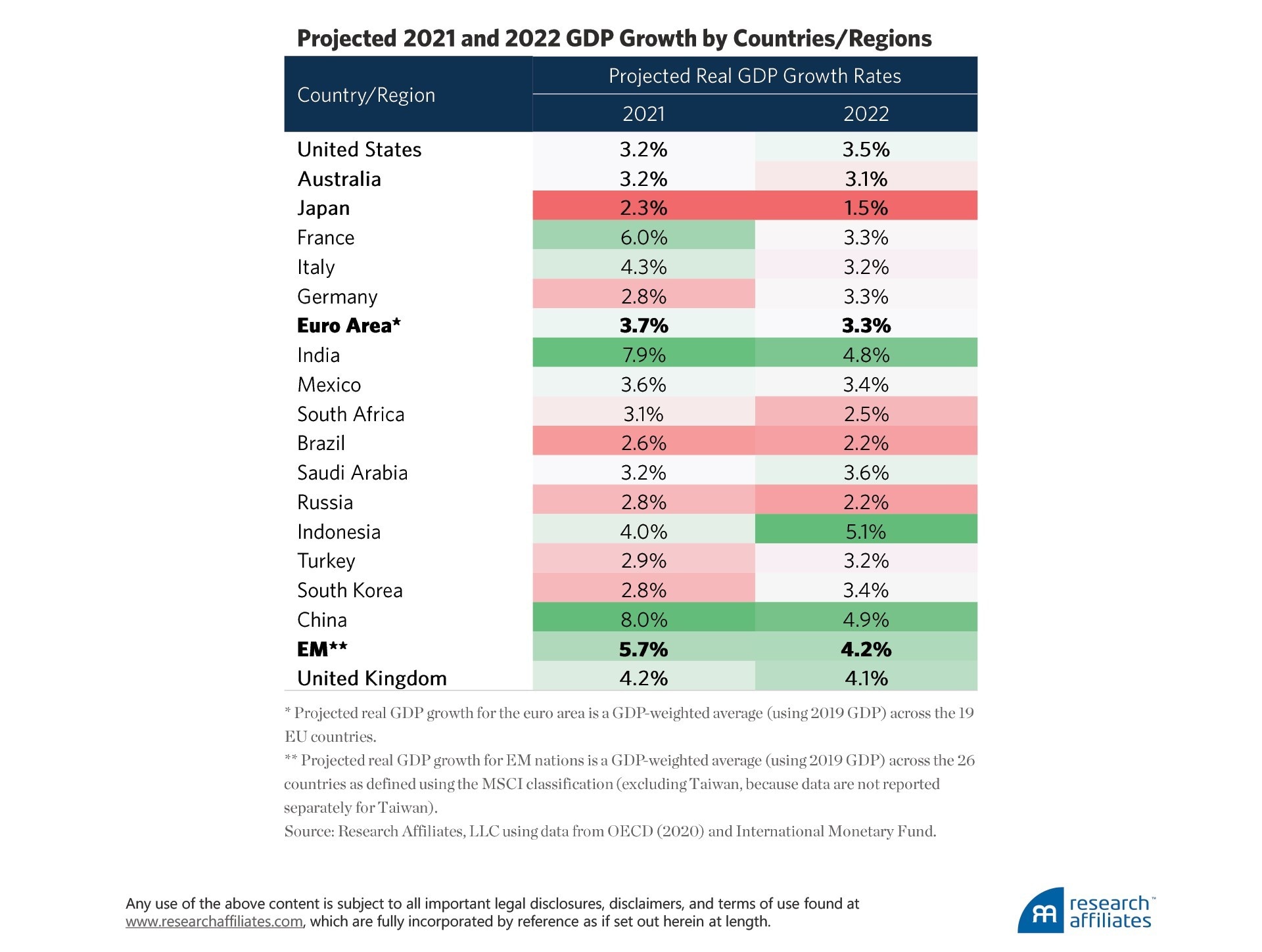

Lastly, the UK’s economy is one of the hardest hit by the coronavirus. The transitory nature of this crisis, as with most crises, suggests that the UK economy should be able to quickly bounce back. The tailwind of vaccination and the clarity around Brexit are responsible for projected UK growth rates in 2021 and 2022 of 4.2% and 4.1%, respectively, which only slightly lag behind the average projected growth rates of the emerging market economies (5.7% in 2021 and 4.2% in 2022).

What does this mean in terms of potential return going forward?

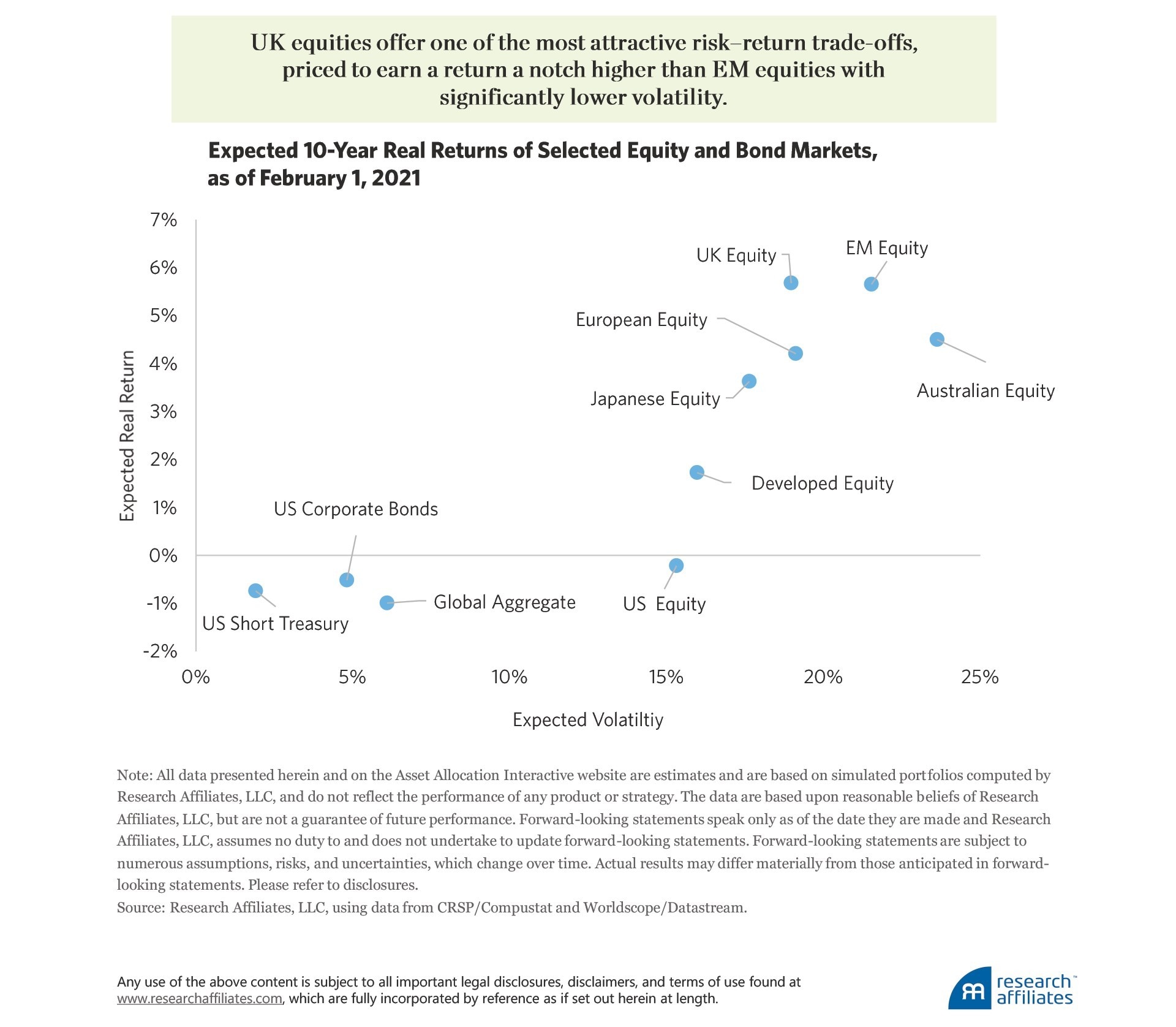

Research Affiliates’ Asset Allocation Interactive web tool uses a fairly simple building-block model that takes into account yield, growth in income, and changes in valuation multiples (or, for bonds, their spreads) to determine the expected long-term return of global asset classes.

Most global asset classes, in particular the majority of fixed-income securities and US equities, are priced to deliver returns below the expected inflation rate, resulting in a negative real return. UK equities stand out as offering one of the most attractive risk–return trade-offs, priced to earn a return a notch higher than emerging market equities with significantly lower volatility.

“For current growth-to-value discounts to be ‘fair,’ [we must] assume roughly half of all value companies will go out of business over the course of the current recession. Obviously, this assumption is implausible.”

This article was originally published on the Research Affiliates website. Part three, which you can find on Opto on Tuesday 16 March, will cover value stocks that the Research Affiliates team have identified as being undervalued.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy