In part one of this two-part series, Ari Polychronopoulos, product manager and head of ESG at Research Affiliates, and John West, a partner in the executive office at the firm, consider whether ESG is a factor worth considering.

Key point:

- Increasingly, investors are asking if ESG is a factor. We answer this question using the criteria set forth by our Research Affiliates colleagues in their 2016 Graham and Dodd Scroll–winning article, “Will Your Factor Deliver? An Examination of Factor Robustness and Implementation Costs.” We conclude that ESG is not a factor.

Abstract:

As we hit the halfway point of this remarkable year, the health of our planet, the well-being of our communities, and the necessity for meaningful societal change are all top of mind and assuming a greater sense of urgency.

Accordingly, many investors desire to take personal action by incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into their investment portfolios. Unfortunately, they are confronted by a confusing ESG landscape with conflicting claims — similar to the multitude of competing health care studies.

This confusion may be slowing down their good intentions. As a factor index provider with ESG offerings, we attempt to answer the question “Is ESG a factor?” by synthesising what we, and our colleagues, have discovered over the years.

Is ESG a factor?

“Can drinking red wine daily stave off heart disease? A newly released study answers that very question. We’ll cover it right after this commercial break.” Does this teaser sound familiar from your favourite morning television or radio show? Does this attention-grabber pique your interest to wait a few minutes, bear the commercials, and hear the story?

The media has a natural inclination to use science to engage audiences. Consequently, we’re bombarded with new studies, especially as they relate to our health, a topic of interest to everyone and, of course, top of mind today.

The findings may entertain, but do they inform? TheJournal of Health Communication finds that contradictory scientific claims on red wine, coffee, fish, and vitamins, all touted by the media, led to substantial confusion on the part of consumers. Indeed, the claims led to such confusion that many consumers grew sceptical of even vetted health advice such as exercising and eating fruits and vegetables. Ironically, learning more about nutrition via competing claims led to more confusion, lack of trust, and less likely adoption of better eating and exercising habits.

As we hit the halfway point of a remarkable 2020 and become more acclimated to our new circumstances, we’re concerned about the health of our planet, the well-being of our communities, and the necessity for meaningful societal change.

Accordingly, many desire to put these concerns into their investment portfolios using environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations and tools. Investors, however, find a confusing ESG landscape with conflicting claims — similar to the multitude of competing health care studies — that may be slowing down good intentions.

As an example, it was John’s turn to represent Research Affiliates at the annual Inside ETFs event in Florida earlier this year. The overwhelming points of emphasis from both ETF and index providers throughout the presentations were factor investing and ESG.

Several sessions covered one or the other, often both. Regardless of whether the headliner was ESG or factor investing, inevitably a question popped up at the end of the session from either the moderator or the audience: “Is ESG a factor?”

"Is ESG a factor?"

If John heard the question six times, he’d venture to guess he heard more than 12 answers! Accordingly, as a factor index provider with ESG offerings, we attempt to answer the question, synthesising what we, and our colleagues, have discovered over the years.

What is a factor, and can we count on it in the future?

Factors are stock characteristics associated with a long-term risk-adjusted return premium. An example is the value premium, which rewards investors who buy stocks that have a low price relative to their fundamentals. Two theories are advanced to explain the value effect: one is risk based and the other is behaviour based.

The risk-based explanation posits that value companies are cheap for a reason, such as lower profitability and/or greater leverage, and thus investors require that they earn a premium to compensate for the risk of investing in them (a risk premium).

The behavioural-based explanation posits that investor biases, such as being overly pessimistic about value companies and overly optimistic about growth companies, create stock mispricing, and that value stocks outperform once investors’ expectations are not met and mean reversion occurs.

Popular factors, such as value, low beta, quality, and momentum, have been well documented and vetted by both academics and practitioners. Research by Noah Beck, vice president at Research Affiliates, Jason Hsu, co-founder of the firm, Vitali Kalesnik, director of research for Europe, and Helge Kostka, vice president, provides a useful framework for determining if a factor is robust, which they outline in the paper “Will your factor deliver?”.

For ESG to be a factor, it should satisfy these three critical requirements:

- A factor should be grounded in a long and deep academic literature.

- A factor should be robust across definitions.

- A factor should be robust across geographies.

A factor should be grounded in a long and deep academic literature

Traditional factors, such as value, low beta, and momentum, have been thoroughly researched and have a track record spanning several decades; very little debate currently exists regarding their robustness. Beyond the size factor, all of the factors in the following table have a positive capital asset pricing model (CAPM) alpha and are statistically significant at the 95% t-stat level (1.96).

In examining the vast body of research on ESG, we find little agreement regarding its robustness in earning a return premium for investors. Research by Clark, Feiner, and Viehs (2015), Friede, Busch, and Bassen (2015), and Khan, Serafeim, and Yoon (2016) finds that ESG is additive to returns, while research by Brammer, Brooks, and Pavelin (2006), Fabozzi, Ma, and Oliphant (2008), and Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) demonstrates that ESG detracts from returns. Neither is there evidence to suggest a risk-based or behavioural-based explanation for the ESG factor.

Arguments are put forth that certain situations could lead to positive ESG-related stock price movements, such as increased popularity of strong ESG companies as more investors adopt ESG (more on this topic later). These price movements, however, would be one-time adjustments and cannot be expected to deliver a reliable and robust premium over time.

Factors should be robust across definitions

Slight variations in the definition of a factor should still produce similar performance results. Using the value factor as an example, the three valuation metrics of price-to-book ratio, price-to-earnings ratio, and price-to-cash flow ratio all yield similar performance results in assessing the factor’s long-horizon performance.

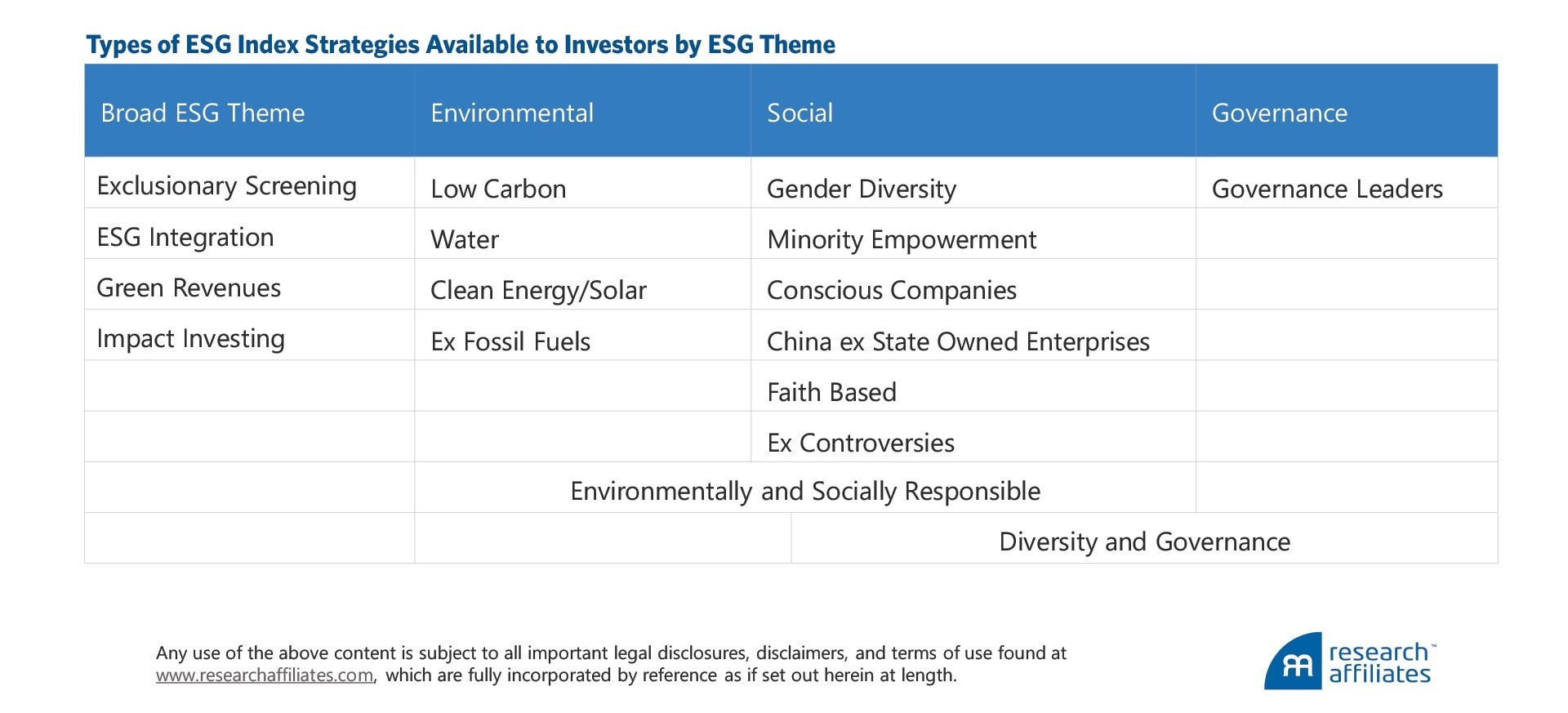

ESG has no common standard definition and is a broad term that encapsulates a range of themes and subthemes. ESG ratings providers examine hundreds of metrics when determining a company’s ESG score.

Conducting a quick web search yields several ESG strategies whose underlying themes are quite distinct and different. These index strategies align more closely with investor preferences than with a particular factor.

To illustrate this, we construct a simple test on four variants of ESG definitions. We build long-short portfolios by selecting the top 30% and bottom 30% of US companies by market capitalisation each year, after ranking by overall ESG rating.

We also build three similarly constructed long-short portfolios, ranking companies on each individual ESG characteristic of environmental, social, and governance. None of these strategies displays a materially positive CAPM alpha except for the environmental long-short strategy, and no strategy is statistically significant at the 95% t-stat level (1.96).

Unfortunately, none of the simulated strategies we tested has a long track record because the ESG data history is quite short. This lack of history is a significant impediment to conducting research in ESG investing, limiting our study period to 11 years from July 2009 to June 2020.

Because multiple decades of data are needed to conduct a proper test, the lack of significance in the t-values is not surprising. Only after several decades of quality ESG data will it be possible to accurately test the claim that ESG is a robust factor.

In addition to the problem of a short data history, the lack of consistency among ESG ratings providers also hinders our ability to determine if ESG is a robust factor. Research Affiliates published findings earlier this year that showed the correlation of company ratings between ESG ratings providers is low.

We illustrated this by comparing two companies, Wells Fargo [WFC] and Facebook [FB] and showed that one ESG ratings provider rates Wells Fargo positively and Facebook negatively, while a second ratings provider ranked them the opposite way.

In addition, we demonstrated that a portfolio construction process using the same methodology, but different ESG ratings providers, can yield different results. While beyond the scope of this article, had we used a different ESG ratings provider for the analysis in the preceding table, we likely would have gotten different results!

Factors should be robust across geographies

We conduct the same study using European companies. The results are largely consistent with the US results. None of the strategies tested has a materially positive CAPM alpha except for the environmental strategy, and no strategy tested exhibits statistically significant CAPM alpha at the 95% t-stat level.

We should note that for the US and European analysis we conduct a simple single-factor linear regression against the market return. In the appendix we present the results of a stricter test using a multi-factor regression that incorporates the value, size, profitability, investment, momentum, and low beta factors.

The multi-factor regression results indicate low or negative alpha for the majority of the strategies. Having put ESG investing strategies through a framework to assess factor robustness, we find that ESG fails all three tests outlined in the paper “Will your factor deliver?”:

- evidence of an ESG return premium is not supported by a long and deep academic literature,

- ESG performance results are not robust across definitions, and

- ESG performance results are not robust across regions.

This article was first originally published by Research Affiliates in July 2020 and can be found on the Research Affiliates website.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy