In part one of this three-part series, Rob Arnott, the founder and chairman of Research Affiliates, and colleagues Vitali Kalesnik, a partner and head of research in Europe, and Lillian Wu, vice president of the firm’s European business strategy, look at how global stimulus packages have impacted value strategies.

Key points:

- Around the globe, value is trading at extremely deep discounts relative to growth. The discounts are wide no matter how we measure valuation.

- While we still like our last-named trade of the decade, emerging markets value stocks, the UK equity market, and UK value stocks in particular, are now even cheaper.

- With the final Brexit deal done and the rapid COVID-19 vaccination rate in the UK, the outlook for value is extremely promising, enough for a “trade of the decade”.

In mid-January 2016, when emerging markets value stocks were extraordinarily cheap, Research Affiliates identified this segment of the market as “the trade of the decade.” In the first two years after the low of 21 January 2016, emerging markets value earned 80%.

The FTSE RAFI Emerging Index, with a value tilt, fared even better with a gain of 85%. In the depths of the COVID-19 crash in March 2020, emerging markets value again settled back to bargain-basement prices, offering investors another bite of the apple.

In late 2020, a new kid emerged on the bargain-of-the-decade block. As Brexit negotiations broke down again and again, and a more virulent form of COVID-19 emerged in the UK, stocks, and notably value, reached implausibly cheap levels relative to justifiably “fair” values of stocks in other developed economies.

We began describing UK value as a new trade of the decade. Even today, UK value remains at remarkably low valuations relative to most of its fundamentals, while enjoying a few fundamental tailwinds.

When the going gets tough

Most investors are transfixed by current events, but surprisingly few will ask: “Will these events matter much in five years?” Neither Brexit nor the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have nearly as much impact in 2026 as in 2020–2021. Therefore, the market shocks induced by these events represent opportunities now.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have an enormous impact on the global economy. Although still too early to tally the numbers, many indicators place the current recession — which is, in many countries, a double-dip recession — among the worst shocks the world economy has experienced over the last century.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the pandemic caused an 8.8% decline in global working hours in 2020, the equivalent of 255 million jobs lost. The ILO measures the impact as about five times as large as the 2009 labour losses arising from the global financial crisis. The 2020 losses disproportionately afflicted the working poor, most of whom do not have the luxury of working from home.

The COVID-19 pandemic is tamping down both the supply and the demand sides of the economy. For example, a survey by the Institute for Supply Chain Management found that “nearly 75% of companies reported supply chain disruptions … due to coronavirus-related transportation activities”, Amitava Sengupta, executive vice president at HCL Technologies, wrote in Entrepreneurs.

The demand side is being impacted as government-imposed restrictions limit customers’ access to goods and services. Notably, few if any of the people making these lockdown decisions are in any risk of losing their job or in need of reinventing their lives for a new economy. In response to both supply and demand shocks, companies continue to cut jobs, further hurting demand as laid-off workers stop spending because their income is reduced.

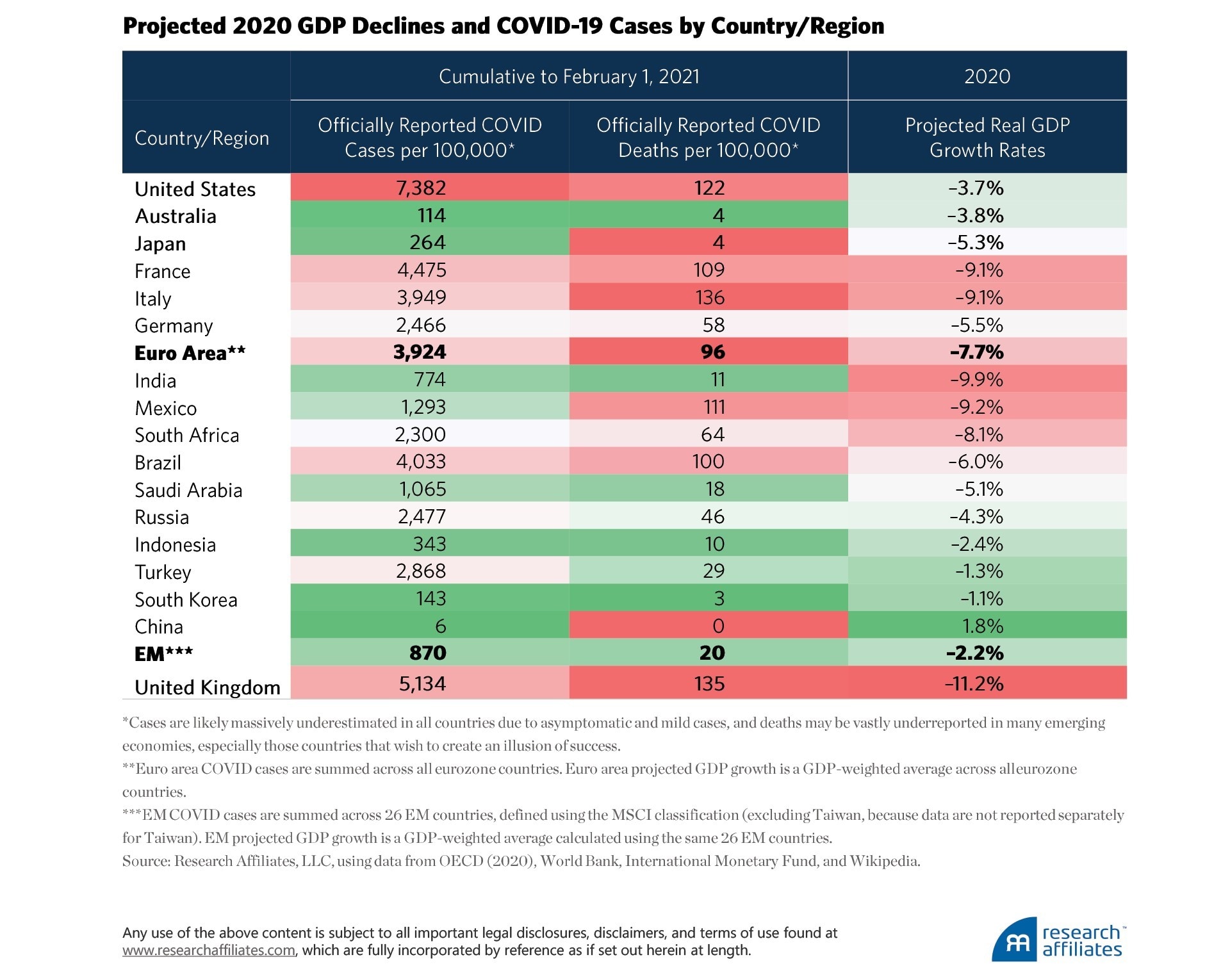

The spread of COVID-19, the resulting lockdowns, and the ultimate impact on national and regional economies have been far from evenly experienced around the world. The developed nations of Italy, the United States, and the UK and the emerging market nations of Mexico, Brazil, and South Africa suffered some of the most devastating personal and economic tolls of COVID-19.

Consistent with intuition, the GDP declines are typically worse among the countries hardest hit by COVID-19. For example, 2020 GDP is expected to decline by 9.1% in Italy and 9.2% in Mexico, and the UK is likely to face one of the deepest GDP declines, currently estimated at 11.2%. The UK’s poor growth outlook reflects the double whammy of Brexit and COVID-19, magnified by Britain’s correspondingly severe lockdowns.

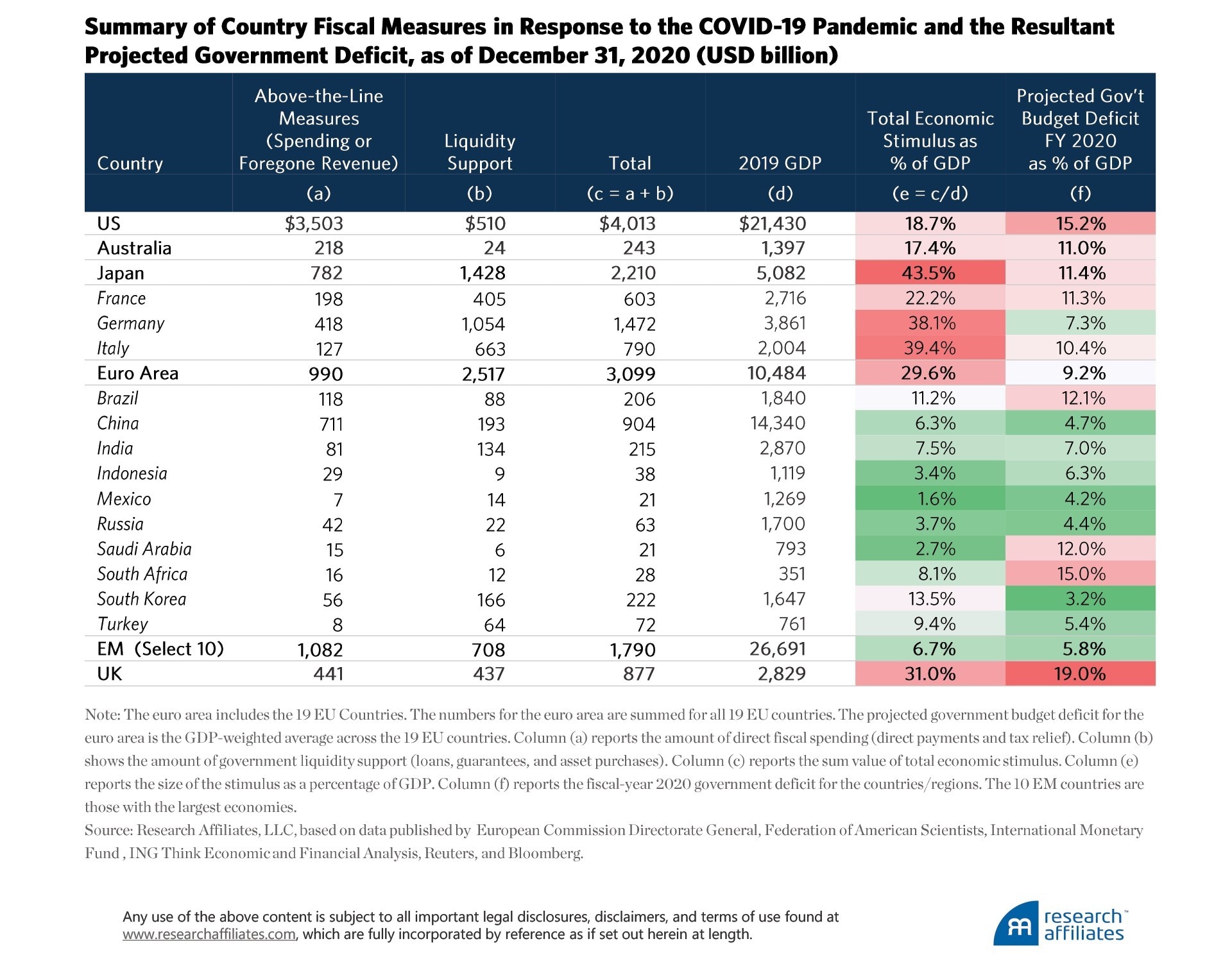

Governments of most major countries acted with unprecedented effort to resurrect their economies and to prevent their financial markets from collapsing. The economic stimulus packages used to provide economic support came in all shapes and forms and included direct payments to companies and individuals, tax deferral, loans, guarantees, and equity investments.

The United States’ fiscal stimulus in 2020 totalled $3.5trn, about 16% of 2019 GDP, three times more than the response to the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, when the stimulus programme was roughly 5% of 2008 GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. The 2020 stimulus took the form of direct payments to individuals, aid to hospitals, funding for medical research, tax relief to companies and individuals, aid to states and municipalities, and a wide array of arguably less-relevant programmes.

The US fiscal stimulus very nearly equals the total combined stimulus programmes of the rest of the world. The $2trn CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act alone marked the largest emergency relief bill in US history. Including the liquidity support the US Federal Reserve Bank provided through quantitative easing, the total value of economic stimulus in the United States as of year-end 2020 approached 20% of GDP.

In Australia, the total value of the economic stimulus program was much smaller (AU$243bn, or US$218bn) than the US programme, but was of similar size (17.4%) relative to Australia’s economy. Ironically, in 2019, the Australian government had just achieved its first balanced budget in a decade. After spending related to pandemic support, the projected Australian budget deficit for 2020 was 11% of the nation’s GDP.

Japan’s COVID-related stimulus package — overwhelmingly focused on monetary stimulus — amounted to 43.5% of its 2020 GDP, the highest of all countries and regions. The Japanese government strongly favoured liquidity support over direct transfer payments to businesses and individuals (2-to-1 ratio). This major stimulus package, and Japan’s ability as an island nation to keep the pandemic at bay, did not save the nation from a 5% slump in GDP.

Western European countries have allocated about US$3.1trn to a diversity of stimulus programmes, about 23 times the inflation-adjusted value of the Marshall Plan after World War II. The UK government’s economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic was massive, valued at about 31% of UK GDP — second only to Japan — sending its budget deficit forecast for fiscal-year 2020 to the most severe level, at 19% of GDP, of the nations we compare. As with Japan, the stimulus failed to avert a severe economic downturn.

Interestingly, across the 10 emerging market nations with the largest economies — Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea and Turkey — the GDP-weighted-average size of the stimulus relative to the combined economies of these nations is 6.7%, far lower than in the developed countries. As with the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 (Faruqee, Das, and Blanchard, 2010), the impact on GDP of COVID-crisis lockdowns has been milder in the emerging market nations.

Perhaps stimulus doesn’t really stimulate?

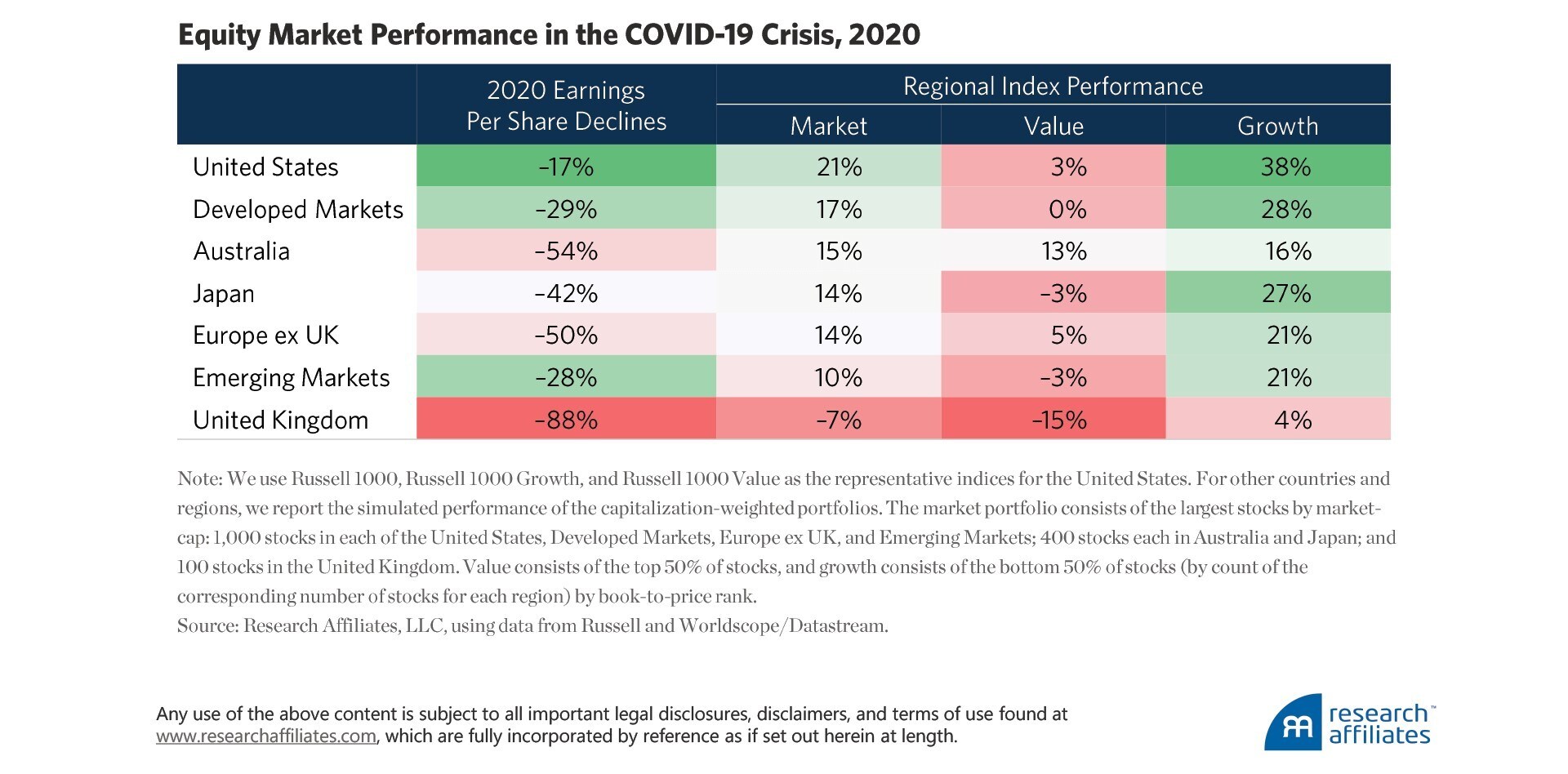

The tremendous shock to the global economy from the COVID-19 lockdowns resulted in dramatic declines in corporate earnings. The European, Australian and UK corporate sectors suffered severe declines in earnings of 50%, 54%, and a staggering 88%, respectively.

In the first quarter of 2021, these nations’ COVID-related economic woes are far from resolved, continuing the global flight to safety and fuelling a surge in prices of US fixed income and equities, giving further support to these asset classes beyond the US fiscal stimulus and the Fed’s deep pockets.

The global flight to safety and the behemoth stimulus packages drove the US equity market to appreciate 21% in 2020. US growth stocks — especially tech companies, in many cases direct beneficiaries of the pandemic — did better still, appreciating 38%.

Meanwhile, value stocks, which experienced slower growth and typically weaker profit margins, were harder hit by the COVID-19 market shock and fared much worse (3%).

Investors’ high-risk aversion to the economic uncertainty of the pandemic significantly weighed on value strategies around the globe, with the exception of Australia. The addition of Brexit uncertainty to the pandemic concerns fed strong negative returns in UK equities in general (-7%) and for value strategies (-15%).

This article was originally published on the Research Affiliates website.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy