In this article, Emily Evans, healthcare policy analyst at Hedgeye, considers the potential effects of politics, policy and power on the burgeoning healthcare special-purpose acquisition company (SPAC) universe.

Politics

Something is sure to go wrong.

Over 400 SPACs have formed and about 100 business combinations have been announced. At least as far as health care goes, excluding biotech and pharma, the quality of the business combinations has thus far been uninspiring.

Deerfield’s [DFHT] CareMax/IMC Medical merger and Jaws Acquisition’s [JWS] Cano Health are focused on the very crowded medicare advantage market just as demographic realities require attention to shift toward younger people.

Falcon’s [FCAC] ShareCare, GigCapital2’s [GIX] Uphealth/Cloudbreak, and Hudson’s [HECCU] Talkspace are yet more digital platforms to manage care. Virgin Group’s 23andMe wants to monetise all the genetic data it has collected through drug development.

As absent durable business models that address the core challenges of health care such as price, efficiency and quality, SPACs seem to be relying on charismatic personalities to win over investors, great and small, regardless of their experience or credibility.

So much so that Twitter entreaties from Chamath Palihapitiya’s fan-base have taken on the tone of religious followers. “@chamath give @Clover_Health some love on Valentine’s Day what’s your position are you optimistic, excited, hopeful of its future? We would love to hear from you…”

The Virgin Group/23andMe combination will certainly produce the most telegenic financing team ever, but investors should wonder what aviation and genetic testing have in common. Other SPAC teams tilt heavily toward technology experience.

The working relationship between Silicon Valley and health care is troubled, to say the least, and likely to continue to be so as demonstrated by Clover Health Investments Corp [CLOV].

There are few targets on Capitol Hill more mouth-watering than the rich and famous. When something goes wrong — an inevitability given the weak standard of disclosure of a Proxy statement — Elizabeth Warren, newly appointed to the Senate Finance Committee, will be waiting with a few questions.

Policy

It is forgotten now, lost in the maelstrom of cries for repeal, constitutional challenges and AstroTurf’d campaigns, but one of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) legacies was to be the launch of a thousand new business models.

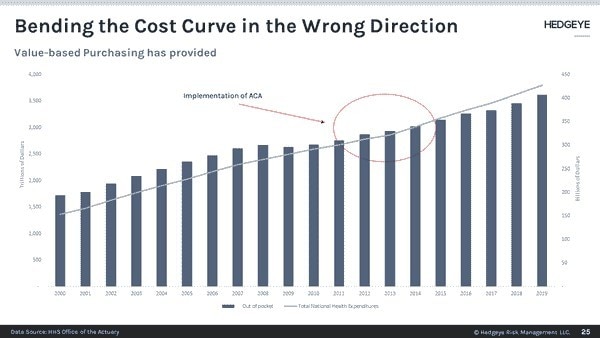

Tested only on paper in the towers of Dartmouth and the University of Pennsylvania, the ACA was to have heralded an era of “bending the cost curve” especially in Medicare through innovative payment models.

Equipped only with old Medicare data, health economists — an ironic title if ever there was one — concluded that federally sponsored programs like bundled payments, Accountable Care Organizations, and coordinated care models would improve outcomes and save the taxpayers money by limiting inappropriate utilisation.

Figuring this approach, known by the short-hand of “value-based purchasing,” would leave them on the wrong end of value-extraction, a few hundred health systems like Tenet Healthcare Corp [THC], the Calamos Convertible Opportunities and Income Fund [CHI], Presbyterian Health in New Mexico and, relevant to our purposes, CareHealth (now known as CLOV) in New Jersey launched provider-based insurers.

Unfortunately for these provider-sponsored plans, we have known since about 2015 that, except in a few areas like post-acute and primary care, value-based purchasing has had little impact on the health care cost curve. In fact, costs accelerated.

Provider-based insurers found it difficult to scale in the face of rising costs and significant institutional bias in favour of higher prices. By 2016, CHI, THC and others had shuttered their plans.

Since then policy has moved on. While it is impossible for many health wonks to outright abandon the faith the ACA has become, even the most devoted quietly recognise that America’s problems with health care have everything to do with price, perhaps a little to do with over-utilisation and nothing to do with who runs the insurance company.

The focus for the next few years, accelerated by COVID-19, will be enhancing productivity, controlling price and, for the next generation of health care consumers, improving the experience.

That leaves us with a lot of middling businesses clinging to hope that the ACA-driven VBC will return triumphant while their investors seek to move on to the next thing.

Power

As Clark Stanley, who moved from town to town in the late nineteenth century selling Stanley’s Snake Oil and ultimately provided the inspiration for the founding of the FDA, well knew, all you need to sell the unsellable was a good story, a charismatic spokesperson and a willing audience.

When it comes to health care SPACs, at least to this point, the formula is the same. Last week Alan Mnuchin’s Falcon Acquisition announced a business combination with Sharecare, headed by the articulate and very convincing Jeff Arnold and complimented by Dr Mehmet Oz as a board member.

ShareCare, based in Atlanta, has been a curiosity for serious health care people for years. It supports employer-based insurance through wellness programs and other tools but is hard to see what else is there to justify a multibillion-dollar valuation.

We must conclude that SPACs in health care may just be the mother of all exit strategies. What better way to escape an ugly business model with little policy support than to allow it to pose beside an attractive advocate, address the uninformed and promise a bright future?

It should work long enough to move on to the next town, or when the lock-up ends, whichever comes first.

This article was originally written as a complementary research note by Emily Evans, healthcare policy analyst at investment research and financial media company Hedgeye. The original article, published on 14 February, can be found here.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy