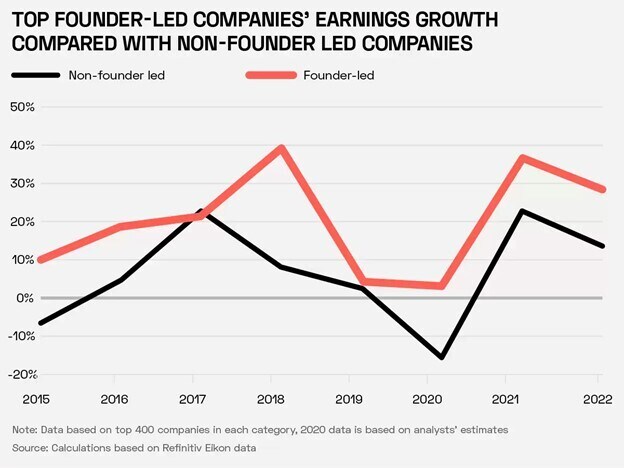

Research shows that founder-led companies tend to outperform their counterparts in a range of areas, including innovation and long-term share price performance.

Understanding the long-term goals of these founders is key for investors seeking to grasp their companies’ full value.

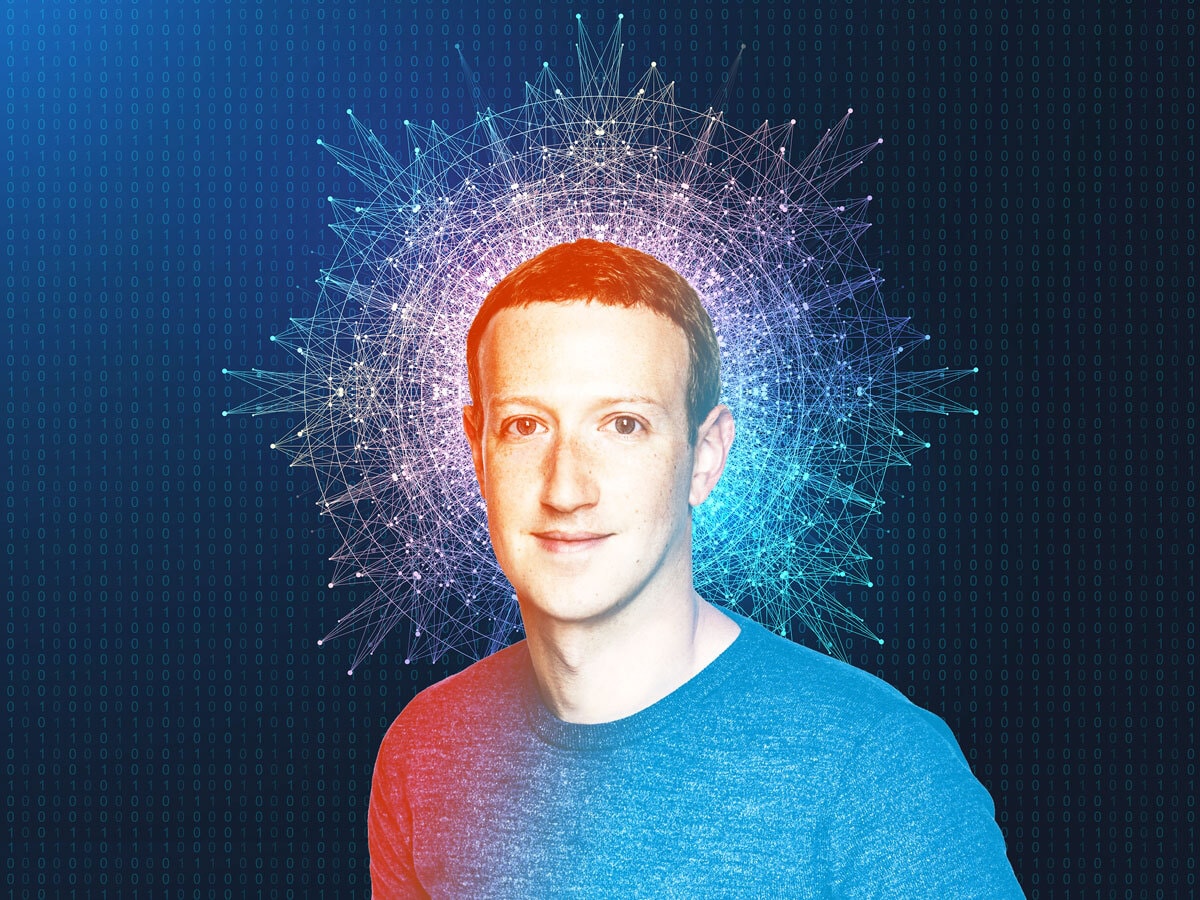

Meta, for example, made a major pivot in October 2021, hinging on its founder Mark Zuckerberg’s determination to spearhead what he saw as the next iteration of the internet, just as he had already done with Facebook.

What Makes Zuckerberg Different? Superficially, Zuckerberg epitomises the quintessential modern tech founder: a socially awkward genius who learned to programme computers by the age of 12 and had already developed a reputation as a coding prodigy before he enrolled at Harvard. Beneath the nerdy exterior, however, there is a highly savvy business mind. Some might even call him ruthless. The biopic of Zuckerberg and Facebook’s rise to prominence, The Social Network, detailed how brothers Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss and Divya Narendra sued him for stealing the initial idea for their site, HarvardConnection.com. This ruthless streak was evident prior to Facebook’s inception. As a second-year student studying psychology and computer science at Harvard University, Zuckerberg hacked into university websites to gather photos of students to populate his site Facemash.com. He escaped expulsion for the misdemeanour, though he eventually dropped out of Harvard to focus on Facebook. Despite the legal challenge Narendra and the Winklevoss twins mounted, Zuckerberg knew he had stumbled on something groundbreaking when he started thefacebook.com. In 2005 — the year after he dropped out of college — Zuckerberg’s Facebook raised $12.7m in venture capital. In 2006, it opened to the general public, and Zuckerberg rejected a $1bn bid from Yahoo! to buy the company. Two years later, aged 23, he became the world’s youngest self-made billionaire. The story of Facebook reflects Zuckerberg’s character: a precocious and explosive game-changer who has never been afraid to stretch the rules in pursuit of revolutionising the social lives of humans. “I’m trying to make the world a more open place” — Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook bio, 2010. |

The Vision

“We are at the beginning of the next chapter for the internet, and it’s the next chapter for our company too,” wrote Mark Zuckerberg on 28 October 2021.

In his founder’s letter to the business that had, until that moment, been called Facebook, and was subsequently known as Meta [META], Zuckerberg detailed the progression of the internet and mobile technology, from text- through to video-based content, and from a desktop- to mobile-based ecosystem. “This isn’t the end of the line,” he promised.

“The next platform will be even more immersive — an embodied internet where you’re in the experience, not just looking at it. We call this the metaverse, and it will touch every product we build.” — Mark Zuckerberg, 2021

Zuckerberg painted a bold, ambitious picture of the future of the internet. He’d earned the right to: Facebook had already completely changed it once.

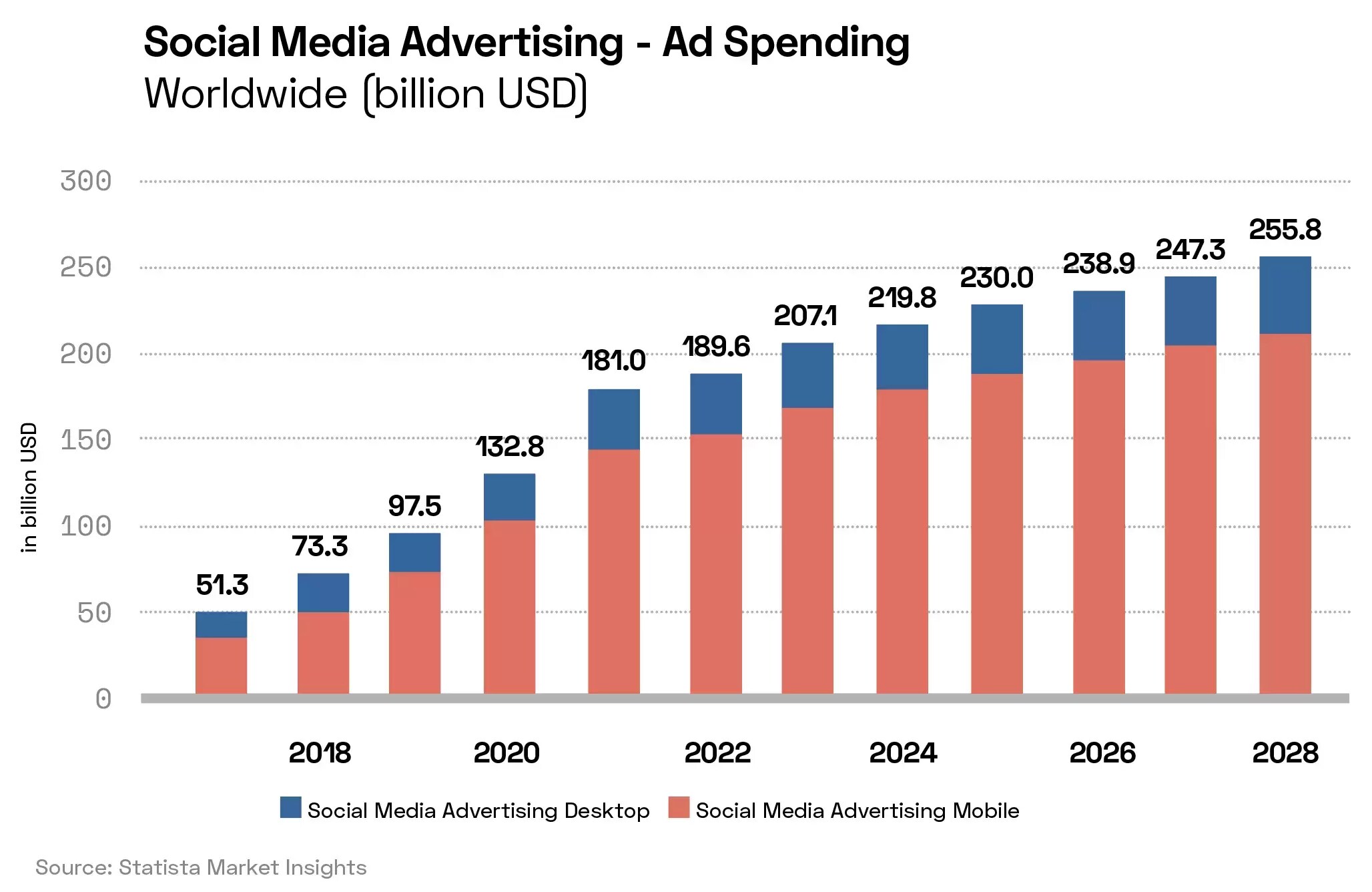

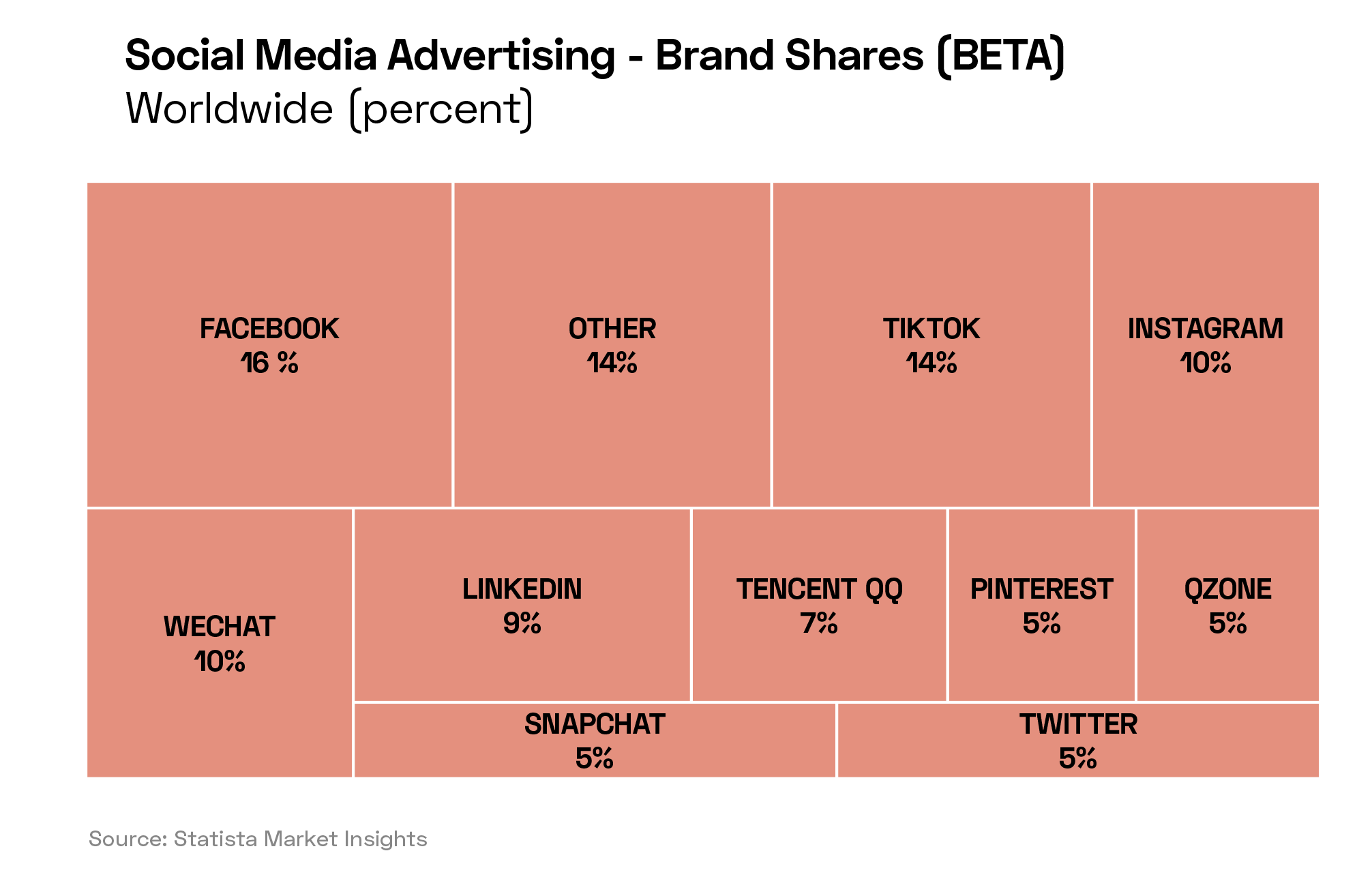

It is easy to forget how transformative Facebook’s impact was. In 2015, the Guardian observed that Facebook had transformed social life, right down to the definition of ‘friend’. Social media had become the key battleground for political campaigns and even revolutions. “Facebook has essentially created an entire sector”, wrote Jessica Elgot for the Guardian, referring to the social media advertising industry which, as of 2022, was worth $189.6bn, according to Statista. Meta, via Facebook and Instagram, accounts for 26% of this industry.

The Plan

According to Meta’s own statement on the day of its rebrand, Zuckerberg’s vision for the metaverse is as “the successor to the mobile internet”. This iteration will, said Meta, “be characterised by social presence, the feeling that you’re right there with another person, no matter where in the world you happen to be”.

Meta’s vision for the metaverse portrayed a world where augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and everyday life came together in one place. It invited citizens of the metaverse to explore open world games like Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas or train their physical bodies in the digital world with Meta’s Quest 2 Active Pack, and promised that the world of work would soon join in with Quest for Business.

“A lot of pieces need to be built before we get to the metaverse proper,” said the statement. The direction of travel was clear, though: Zuckerberg’s Meta was bringing about a world where the online world that Facebook had pioneered was less and less distinct from the real one.

Progress?

Blurred Vision?

In many ways, this vision of the metaverse was a product of its time — a sales pitch to a carbon-conscious world that had spent nearly two years adjusting to the sedentary life of the Covid-19 pandemic:

“In this future, you will be able to teleport instantly as a hologram to be at the office without a commute, at a concert with friends, or in your parents’ living room to catch up. This will open up more opportunity no matter where you live. You’ll be able to spend more time on what matters to you, cut down time in traffic, and reduce your carbon footprint.” Mark Zuckerberg, 2021

Once the initial hype died down, society’s digital metamorphosis proved underwhelming. A year after Meta’s rebranding, Insider Intelligence cited a Sitecorp survey that found only 27% of advertisers strongly agreed with the statement “There will be widespread adoption of metaverse technologies for consumers and brands”. According to the New York Times, rifts had reportedly opened in Meta’s boardroom around the company’s spend on unproven metaverse projects.

The world had already seemed to move on, and Zuckerberg with it. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) was the shiny new toy in late 2022 and early 2023, and it began to draw more of the founder’s focus. TheStreet reported in March that Zuckerberg had “quietly” buried the metaverse, with Reality Labs, the unit responsible for developing the technology behind it, $24bn in the red. Instead, Zuckerberg sought to “turbocharge” the company’s work on generative AI, according to a post he shared on Facebook on 27 February 2022.

An End in Sight?

However, The Verge reported in September that Zuckerberg has not lost sight of the end goal. “Whatever Meta does is the metaverse, by definition — at least for Mark Zuckerberg,” wrote Laura Martins for the technology media site. In her article, ‘Mark Zuckerberg Can’t Quit the Metaverse’, Martins explained how, while the focus appears to have shifted, much of Meta’s work on AI could feed back into the metaverse in the long run.

The recent launch of ‘smart glasses’ in collaboration with Ray-Ban is a case in point. In 2022, Zuckerberg told The Joe Rogan Experience that replacing cumbersome, insular VR headsets with AR glasses is key for the metaverse to become truly integrated with everyday life.

AI in various forms will be integral to Zuckerberg’s metaverse. During his interview with Joe Rogan, Zuckerberg voiced his desire for more responsive facial recognition (i.e., computer vision) technology, to enable avatars to mimic their users’ facial expressions.

Smart glasses incorporate Llama 2, Meta’s large language model, and respond to voice commands. ARK Invest calls the product’s incorporation of AI technology “the first killer feature for smart glasses — and the most compelling case for hands-free computing yet”.

The metaverse will not be a sudden revolution; that much has become clear in the two years since Zuckerberg announced his vision. Its technological underpinnings will, however, continue to evolve, and consumers will increasingly shift towards the online world over time.

Investment Takeaway

If seen through a purely performance-focused lens, AI has been better for Meta than the metaverse has. In the year following the rebrand, Meta’s share price fell 68.7%; in the year to 24 November 2023 (a few days shy of ChatGPT’s first anniversary), the stock has gained 206.5%.

In a further display of the interconnectivity of technological development, however, it should be noted that during the first of these periods, Apple [AAPL] changed its privacy settings, contributing to a torrid earnings report, and Meta posting the largest single-day loss of market value in stock market history.

Investors seeking diversified exposure to companies building metaverse technology can select a metaverse ETF such as the Roundhill Ball Metaverse ETF [METV]. As of 23 November, Meta is the fund’s third holding, with a 6% weighting. As of 30 September, the fund offers exposure to gaming platforms (23.5%), computing components (21%), cloud solutions (16.1%), social networks (9.7%) and other segments (29.3%). METV gained 37.2% in the 12 months to 24 November.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy