In this article, RBC Wealth Management’s Atul Bhatia considers how potential Fed rate hikes will affect the investing environment.

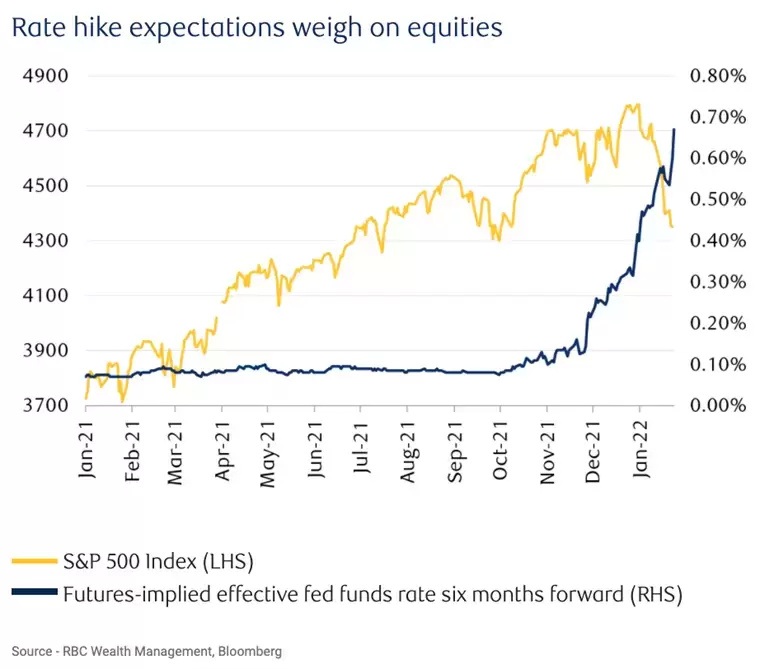

Global equity markets experienced significant volatility this past week, with several major indexes, including the S&P 500, dropping more than 10% from recent highs during intraday trading activity.

A combination of factors contributed to the selling pressure, including continued concerns about inflation, uncertainty around the potential impact of the Federal Reserve’s shift to less accommodative monetary policy, profit-taking following a very strong nearly two-year appreciation in stocks, and geopolitical tensions.

While the geopolitical picture is still unclear, the Fed reduced some of the uncertainty around the policy framework at its recently concluded January meeting. The Fed’s post-meeting statement — and comments made by Fed Chair Jerome Powell — confirmed our expectations as well as market pricing, by guiding investors to a March rate hike, which would be the first of the tightening cycle.

The balance of risk monetary policy

While policy mistakes are always possible — and some could reasonably argue that the Fed already made one by continuing with bond purchases for such a lengthy period — it strikes us as unlikely that the Fed will push the economy into recession through higher rates. The current inflationary pressures are coming largely from supply disruptions, and we believe the Fed’s primary game plan is to cool monetary policy to the point that it is not further aggravating inflationary pressures, allowing supply-chain issues time to resolve. Since the Fed’s goal is a somewhat limited one, we believe policymakers are unlikely to push on the brakes so hard as to tip the economy into recession.

One reason for our relatively benign view on rate hikes is experience. Both the Fed and market participants, we believe, have a fairly well-calibrated sense, developed over decades, for the likely impact of a quarter- or half-point rate hike.

Rate hikes also operate largely through the banking system. Since the Fed is both a central bank and a banking regulator, it has a multitude of formal and informal channels to receive feedback on how policy moves are impacting the real economy. This offers the Fed much greater transparency on rate moves relative to balance sheet size, where impacts extend more directly to non-banking entities.

Excess liquidity may not be excessive everywhere

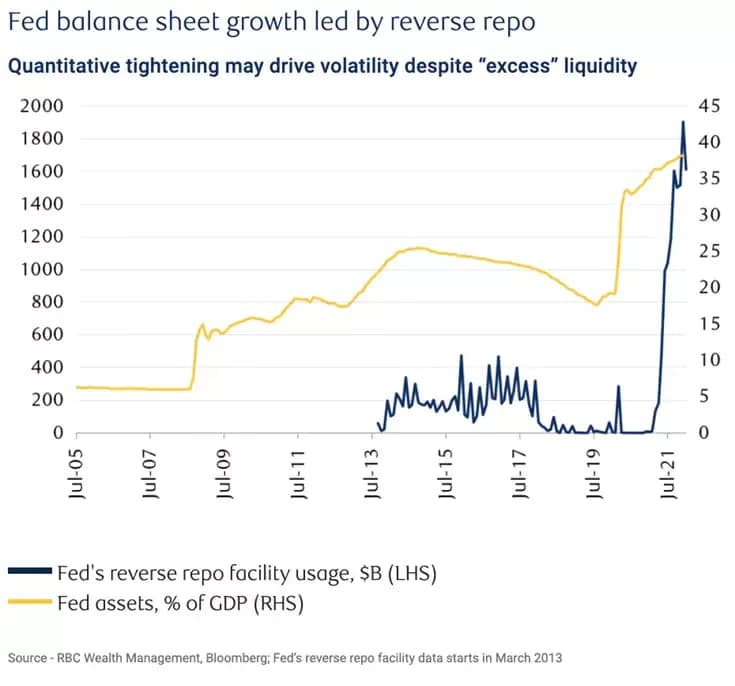

Although we do not see rate hikes as a likely source of significant long-term economic concern, we do see the potential for higher volatility across markets as the Fed tightening progresses, particularly when the central bank begins reducing its balance sheet, a process known as quantitative tightening (QT).

Concerns about QT may seem like an issue for a distant date, given the amount of liquidity the Fed has created with asset purchases. Its balance sheet is approaching $9trn, or a record 38% of GDP; prior to the global financial crisis the balance sheet hovered around six percent of GDP and even at its post-financial crisis highs, Fed assets had never previously risen above 26% of GDP.

Most tellingly, market participants have placed nearly $1.5trn in the Fed’s reverse repo facility, essentially choosing to return liquidity to the central bank rather than use it directly. With that amount of excess liquidity already parked at the Fed, which we believe will take the Fed at least a year to draw down, it may seem that concerns about balance sheet liquidity are a matter for 2023 or later.

History, however, points in a different direction. In 2019, the Fed reduced its balance sheet from approximately 20% of GDP to just over 17% of GDP as part of its last round of policy normalization. Although the balance sheet after the reduction was nearly three times its size prior to the financial crisis, the relatively small contraction caused a meaningful — but temporary — dislocation in bond financing markets. The Fed quickly stepped in to provide the needed liquidity, and it has since created a $500bn standing facility to avoid any repeats of the issue during this round of QT.

We see the potential for similar, temporary disruptions as liquidity becomes more restricted in the interdealer market as the Fed’s balance sheet shrinks. But like the September 2019 hiccup in Treasury repo markets, we believe the Fed has ample tools to deal with liquidity disruptions, including partnering with the Treasury Department to provide temporary support to a wide range of markets. So, while the uncertainties associated with QT may bring volatility, we do not see a high risk of permanent impairment to asset prices.

Preparation is key

With policy shifting from accommodative to more restrictive, and with the recovery entering a slower growth phase, investors likely need to adjust their expectations to periodic bumps in the road. But as RBC Wealth Management’s Global Portfolio Advisory Committee highlighted in a recent market update, the key issue for investors is if the headwinds and turbulence are sufficient to push the real economy into recession.

At the moment, we do not see the market signals that typically precede an economic contraction, and as such we remain constructive about the path for equities and risk assets.

We believe this week’s price volatility across markets is a salutary reminder of the need to be prepared for temporary dislocations in markets, both to prepare portfolios and to avoid hasty decisions.

This article was written by RBC Wealth Management and originally published on the firm’s research and insights page, here.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy