In this article, Martin Alvarez, chief commercial officer at The Long Term Stock Exchange (LTSE), considers the benefits and pitfalls of special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs).

Some of us on occasion indulge in a little fast food. We duck into a drive-thru, park in the first space we find and partake — all while hoping that no one we know is watching.

Yet I wager that few of us have ever found our way to Burger King after contemplating the relationship between cicadas and sesame seeds to help fund portfolio companies. That honour rests with the late Peter Gregory of “Silicon Valley.”

As it happens, Burger King went public via a special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, for $1.4bn in 2012 [before becoming part of the Restaurant Brands International group [QSR] in December 2014]. Though SPACs have been around since the late 1990s, they are experiencing a renaissance lately.

To add to the irony, Bill Ackman, the hedge fund manager who backed the Burger King SPAC eight years ago, has just raised $4bn to fund the largest SPAC in history.

Much like fast food, going public via a SPAC is quicker and easier than via a traditional initial public offering. But like a Double Whopper with cheese, a SPAC may cause some indigestion afterwards. Still, SPACs, like direct listings, may appeal to some companies as an alternative to a conventional IPO.

The discussion that follows gives an overview of SPACs, runs down their use, and examines their suitability for companies that want to go public.

SPAC basics

SPACs are so-called blank-cheque companies that are formed to raise capital in an IPO. They are blank cheques because SPACs use the proceeds from the IPO to buy one or more businesses to be named later. SPACs have management teams that are known as sponsors.

Sponsors of SPACs typically include managers of hedge funds and private equity funds. Sponsors may establish a mandate to acquire a business or assets within an industry or sector that mirrors their expertise. Thus, most SPACs focus on a particular industry.

As with a typical IPO, a SPAC files a registration statement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, puts on a road show, and raises proceeds by selling equity to public investors. In short, the SPAC, as a blank-cheque entity, puts up with the IPO process so its future acquisition target doesn’t have to.

However, target companies still have to prepare themselves for the public markets. They must reinforce executive teams and support staff to be public-ready, implement new systems and internal controls, and conduct audits and cure material weaknesses, to name a few necessities.

Though SPACs make it easier to go public, they can make it harder to be public. Companies should consider the trade-offs of managing traditional IPO workflows while still private compared with managing the dynamics of a SPAC in the public eye.

SPAC mechanics

Investors in a SPAC IPO typically buy equity units that consist of two components: one share of common stock and a fraction of a warrant. The fraction of the warrant per share of common stock is often referred to as warrant coverage, which compensates investors for the risk associated with investing in a blank-check company.

The equity units are separable, meaning that investors are able to trade the entire equity unit or its components — the common stock or warrants. The equity unit, the common stock and the warrants are listed individually on a securities exchange. Most warrants have a five-year term.

Typically, warrant coverage ranges from 33% to 50%, meaning that each equity unit carries one share of stock and one-third to one-half of a warrant. By contrast, Bill Ackman’s record-setting SPAC offering includes 200 million units at $20 each (for a total of $4bn). In that offering, each unit consists of one common share and one-ninth of a warrant that can be exercised at $23.

SPACs store the proceeds from their IPO in a trust until the sponsors buy something, which they’re typically required to do within two years of the public offering. Before agreeing to acquire a company, the SPAC will often line up commitments from investors to finance a portion of the purchase. Then the SPAC will announce both the acquisition and the financing to help pay for it. This is how a $500m SPAC goes about acquiring a multi-billion dollar company.

In most instances, after a SPAC announces a proposed deal, the SPAC’s public shareholders get to vote on it. Those that choose to pass on the vote are entitled to return their shares (but not the warrants) to the SPAC in exchange for an amount of cash roughly equal to the IPO price. In addition, existing shareholders of the target operating company will likely become equity holders of the acquiring SPAC.

If the SPACs shareholders OK the deal (assuming that’s required) and the financing and other conditions specified in the acquisition agreement are satisfied, the SPAC and the target business will combine into a publicly traded operating company.

History of SPAC activity

Though SPACs emerged in the late 1990s, their use surged in 2004. That’s no coincidence: The timing parallels the rise of hedge funds and aligns with a shift toward short-term thinking in public markets. Hedge funds love SPACs mainly because hedge funds love the warrants. (More on that in a moment.)

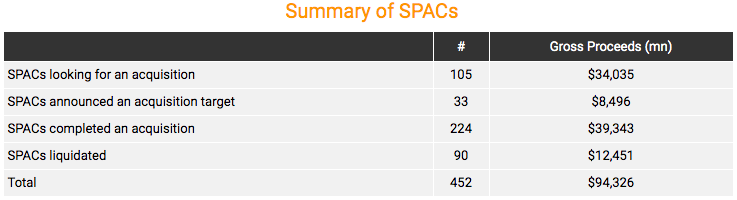

Since 2003, SPACs have raised more than $94bn. In 2020 alone, companies going public via SPACs raised roughly $25bn, or circa 40% of total IPO proceeds raised year to date (through 12 August). We saw a similar surge in SPACs in the run-up to the Great Recession.

The recent fascination with SPACs seems to be fuelled, in part, by Virgin Galactic [SPCE], DraftKings [DKNG] and Nikola [NKLA], which each merged with a SPAC to become public.

SPACs also are making a splash in ways similar to direct listings.

Investors such as venture capital firms who invested in a company early may welcome the ability to exit via a SPAC, which frees them from the lockup that comes with a conventional IPO.

Summary of SPAC activity since 2003

Source: SPAC Analytics (as of Aug. 9, 2020)

Happy Meals for hedge funds

The investors in SPACs tend toward hedge funds, which use SPACs as trading vehicles to run a fairly typical playbook: buy the unit, sell the stock, keep the warrants and gamma hedge the warrants.

Gamma hedging aims to profit from volatility. Gamma hedging warrants refers to a trading strategy where an investor (think hedge fund) goes long on the warrant, shorts the stock as a hedge, and rebalances that hedge as the stock rises and falls (increasing the short as the stock rises and decreasing as it falls). Hedge rebalancing is designed to capture small trading gains whether the stock goes up or down.

Merging with a SPAC means your company inherits a base of shareholders that’s dominated by hedge funds. This means your shareholders will be more focused on monetising warrants through gamma trading than on your company’s long-term fundamentals. In essence, you begin public life as a trading vehicle.

It can take years to shake off trading-vehicle status. The transition comes down to persuading longer-term shareholders to buy shares from short-term shareholders. But that takes time. Remember, most warrants in a SPAC carry a five-year term.

There’s more.

Hedge funds are happy to sell their common stock while keeping the warrants. While that helps to ensure a supply of shares for long-term investors to buy, the hedge funds will continue to gamma hedge. As noted, pre-IPO shareholders like venture capital firms may also look to exit the stock. This activity can frustrate the aims of long-term investors.

For simplicity, think of trading volume related to gamma trading as artificial liquidity. Artificial liquidity becomes a problem when the number of outstanding warrants is high in relation to a company’s average daily trading volume.

If artificial liquidity represents a large percentage of average daily trading volume, then gamma trading can depress, or cap, a stock price. This can become acute if a company’s shares trade within 10% of the exercise price of the warrant. The disadvantage gets magnified during the last year of the five-year term of the warrant. That’s when gamma traders hedge like crazy.

Not surprisingly, the dynamic dealt by gamma trading, together with unrestricted sales by pre-IPO shareholders, can sour the experience of even the most bullish long-term investors; the very investors that the company has worked to persuade to buy its stock.

Moreover, sales by hedge funds of common stock (whether through outright sales or through shorting) and pre-IPO shareholders may sap demand a company may be counting on for capital raises to come. The result: The capital raised by a company that goes public through a SPAC can cost a lot more than the capital that a company could raise via a traditional IPO.

Traditional IPO performance and SPAC performance converging

In my recent post on direct listings, I discussed how such listings hold appeal for companies that everyone expects to be hot IPOs. Historically, at least, SPACs are the opposite. For most companies that use them, a SPAC may have been the only viable alternative for the company to get public. It’s why SPACs are structured with a short-term orientation.

There are some signs of change. As the examples of Virgin Galactic, Nikola and DraftKings suggest, some companies — especially if they have big brands, a sizable number of customers and a strong base of shareholders from the start — can pull off a SPAC as a credible substitute for a traditional IPO. Such companies may also enjoy a volume of average daily trading that helps to offset the effects of gamma hedging.

The recent formation by Therapeutics Acquisition [RACA] of a healthcare-focused SPAC marks another step toward turning SPACs into a better IPO alternative. The blank-cheque company is the first of its kind to go public without warrants. (It planned to use warrants but later removed them.)

By some measures, the performance of SPACs and traditional IPOs appear to be converging. Since 2017, the performance of companies that went public in a SPAC has more closely tracked (and in some instances matches) that of companies that use a traditional IPO.

That said, roughly 60% of SPACs that have completed acquisitions this year trade below issue. The pattern mirrors the performance of SPACs that completed acquisitions in 2019.

The canary in the capital markets coal mine

Historically, the fundamentals of companies that merge with a SPAC do not match those that went public in a traditional IPO. By design, SPACs aim to mitigate that risk for investors primarily by providing them with warrants.

Merging with a SPAC may help your company go public, but it ties your company tightly to investors who may not share your vision or commitment to building a sustainable business over time. That’s not to suggest such investors aren’t out there: You’ll have to work very hard to connect with them and even harder to keep them.

That’s also not to say that SPACs don’t deserve a place in capital markets. Or that merging with a SPAC isn’t a workable way for some companies to go public. But when you see SPACs raising record sums of capital, take it as a warning that the markets will tilt even further toward the short term.

This article was written by Martin Alvarez, the chief commercial officer at LTSE, a firm offering software, advisory services, and a public-market option. It was originally published on the LTSE blog, here.

Continue reading for FREE

- Includes free newsletter updates, unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy