Whoever came up with the line “events dear boy, events”, may well have had politics in mind, but this phrase could equally be applied to events in the financial markets in 2020. It's a year which will go down in history as one of the most challenging in decades, and which made mugs of us all in terms of predictions of where markets might go.

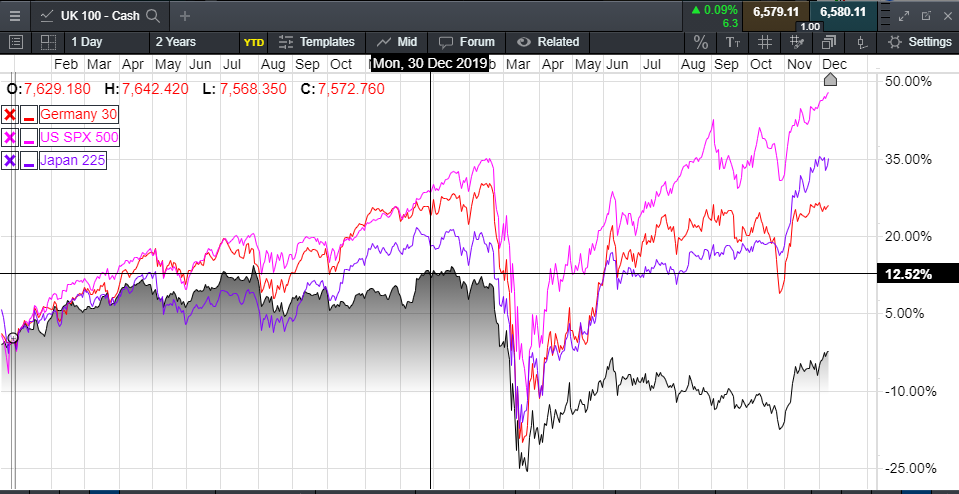

One of the most notable trends of the last few years has been how the FTSE 100 index has underperformed relative to its peers. We can assign any number of reasons for this failure to keep up with the likes of the DAX, Nikkei 225 and the S&P 500, one of which is the 2016 Brexit vote, which saw the UK vote to leave the European Union. Since the outcome of that vote became known, the FTSE 100 has gone pretty much nowhere, despite the fact the pound is around 20% weaker on an exchange rate weighted basis since that vote.

Compare that to the performance of the S&P 500, which is up almost 70%, the Nikkei 225 which is up over 50% and the German DAX which is up over 25%, and it’s hard to argue that the FTSE 100 has seen a pretty poor return over the past few years.

A lot of the blame for the underperformance of UK assets has been laid at the door of that vote outcome, and while there may be some truth in that in terms of the political and economic uncertainty that has come about as a result, it’s also incredibly lazy thinking. For a start, the FTSE 100 has barely gone anywhere in the last 20 years, so the fact that the UK’s benchmark index has underperformed is not entirely down to the 2016 Brexit vote.

It was only in the months after the Brexit vote that the index was able to maintain a foothold above the 7,000 level and its previous 1999 peaks of 6,950, for any length of time, staying there for almost three years, bar a brief two-month period in 2019 that saw a dip down to 6,530.

UK 100 performance comparison since 2019

Source: CMC Markets

At the end of 2019, the FTSE 100 was still able to post a fairly decent 12.5% gain, and while that lagged well behind the S&P 500, DAX and Nikkei 225, it’s important to remember we’re not comparing like with like.

Starting with the S&P 500, this index saw a huge number of US companies buy back their own shares in response to various tax changes brought about by the Trump administration, which in turn boosted their valuations. This has been a consistent theme among US companies since 2016, while the German DAX is a total return index, which includes dividend reinvestment. If we looked at the FTSE 100 as a total return index over the same period, it would also be up by over 20%.

To finish off the comparison, the Japanese Nikkei 225 has been helped by large-scale ETF buying by the Bank of Japan, which has helped boost this index to its highest levels in nearly 30 years.

When the FTSE 100 is looked at through this prism, it is then less surprising that the index has underperformed and that theme has continued this year, when we fell back sharply below the 7,000 level, as well as below the lows in 2019 of 6,530, as it became apparent that the coronavirus pandemic was going to result in a large-scale once in a lifetime economic shock.

The big question now is what happens next, and that’s a harder question to answer, given that we are still in the midst of the pandemic’s second wave, and the prospect of a vaccine, while now available will take some time to deliver upon, as it gets rolled out.

UK 100 performance comparison 2020 year-to-date

Source: CMC Markets

It’s notable that once again the S&P 500 has managed to outperform, hitting new record highs, despite the economic shock of the pandemic, while the Nikkei has also seen a decent rebound.

The response of the US Federal Reserve has certainly helped in this regard, with a number of new monetary policy interventions which almost stray into the realms of fiscal policy. Various lending programmes, along with the purchase of so-called “fallen angels” corporate debt have almost acted as a put against bankruptcy of a number of large US companies.

It is also interesting to note how different the pace of the respective bouncebacks has been, and how much harder the FTSE 100 has been hit relative to its peers, though if you dig deep enough below the surface it’s also easy to understand why the FTSE has struggled.

So, while the FTSE 100 has clearly struggled this year, it also stands to reason that it could also be the most susceptible to a strong rebound, if the UK and global economies see a normalisation in 2021, with the prospect of a move back above the 7,000 level a likely possibility, and higher towards 7,400.

The sectors hit the hardest by the pandemic: travel, leisure, general retail, energy and banks, all of which make up a significant proportion of the FTSE 100, encapsulates quite neatly why the FTSE 100 has been hit as hard as it has, and that’s before we even consider that the Brexit transition period comes to an end at the end of this year. If we look at the likes of IAG, down over 60%, Rolls-Royce, BP, Royal Dutch Shell and Lloyds Banking Group over 40% lower, and NatWest Group, more than 30% weaker, the evidence is clear to see.

The rebound in the German DAX has also been fairly impressive, however there are concerns as we look ahead to 2021. While there is no question that all the major central banks are likely to remain in full easing mode for the foreseeable future, the major risks for 2021 are in terms of fiscal policy, and thus far the lack thereof, particularly in Europe, and to a lesser extent in the US under the new Biden administration. The direction of travel in respect of the European growth story still remains a concern, as it has been for the last two years.

The pandemic has hit Europe’s weakest economies the hardest, notably Italy and Spain, and while the agreement to put together a new EU €1.8trn budget, with a component that allows the raising of communal debt to the tune of €750bn, is a welcome development, the deal rather smacks of symbolism more than any actual desire to move towards a fully-integrated approach. The conditionality around the loan component is likely to prompt governments to step back from going down that road, while the grants are likely to be far too small to make a difference.

Dissatisfaction with the EU still remains a clear danger to politicians across Europe, and while the European Central Bank has seen Christine Lagarde slip into the shoes of Mario Draghi as president of the ECB, it remains to be seen whether she can take the rest of the governing council with her when it comes to filling the vacuum created by the lack of a bazooka type of fiscal response.

One thing that also hasn’t gone away is the fragility of the European banking system, which the pandemic is likely to strain further, as more and more companies run the risk of collapsing under the weight of their inability to trade through the various lockdowns. It seems absolutely astonishing to me that European banks haven’t set aside the sums that UK and US banks have, in the context of non-performing loans, and if this issue isn’t addressed sooner rather than later, then the EU could well find its cohesiveness tested further in the weeks and months ahead.

As far as the US is concerned, while the economic rebound has been much more impressive, it is clear that a second fiscal stimulus programme is likely to be necessary. At the moment we have no idea whether or not we will get one, and if we do how large it will be. There is no question that the new US president-elect, Joe Biden, wants to implement a big fiscal plan, however a failure to secure a Senate majority will mean he will be a hostage to the Republicans, who will be able to block anything they don’t like for at least the next two years.

The UK remains in a slightly better position, given that the UK government has already extended the furlough programme until March next year, in order to prevent significant long-term economic damage to the wider economy, but even here the UK recovery will still need the uplift of a broader European and global recovery. This means that further equity market upside could well be contingent on prolonged fiscal support as we head into 2021.

Disclaimer: CMC Markets is an execution-only service provider. The material (whether or not it states any opinions) is for general information purposes only, and does not take into account your personal circumstances or objectives. Nothing in this material is (or should be considered to be) financial, investment or other advice on which reliance should be placed. No opinion given in the material constitutes a recommendation by CMC Markets or the author that any particular investment, security, transaction or investment strategy is suitable for any specific person. The material has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research. Although we are not specifically prevented from dealing before providing this material, we do not seek to take advantage of the material prior to its dissemination.